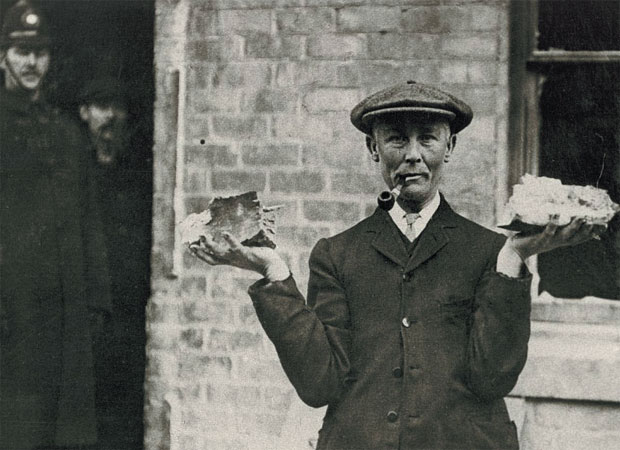

A man holds up fragments of German shell in Hartlepool – such fragments were very soon afterwards being sold a souvenirs

BISHOP Auckland had never seen anything like it. The unpolished oak coffin, wrapped in a Union flag, led a procession more than a mile long through the streets to the cemetery.

There were so many wreaths and floral tributes that they couldn’t all fit in the funeral coach, and so some had to be carried by the hundreds of soldiers behind the coffin.

MAINLAND ATTACK: Cleveland Road, Hartlepool, after the bombardment of 100 years ago

Thousands of people lined the route, no doubt bowing their heads as the coffin passed and the Durham Light Infantry band played Handel’s sombre Dead March.

This, on Monday, December 21, 1914, was Bishop Auckland’s first taste of the horrors of the First World War.

KILLED: Private Walter Rogers

The victim was Private Walter Rogers, 25, who, five days earlier, had been among the first people to die on home soil during the war. As Memories 157 told, on December 16, 1914, three German warships had unexpectedly opened fire from a mile out on Hartlepool.

The flagship battlecruiser Seydlitz fired the first shells at the Heugh battery on the Headland, which was guarded by members of the 18th (Service) Battalion of the DLI.

They were volunteers who had responded to the call by Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, to form “pals” regiments – groups of friends who all joined up together.

For the previous six weeks, the County Durham Pals had been billeted at West Hartlepool for training purposes, and this was their first, terrifying experience of war.

Five Durham Pals died in the bombardment, earning them an unwanted place in British history. Corporal Alix Liddle, of Darlington, was one of the first to go down, and Pte Rogers rushed to his aid.

“He was killed while in the act of covering up Cpl Liddle, who was cut up with one of the first shells,” said the Northern Despatch newspaper. “Pte Rogers received the full force of another splinter from a shell in the chest, but he lingered for three hours.”

Following Memories 157, reader Paul Dobson has researched Pte Rogers’ family tree.

His parents were Arthur, a lithographic printer from Wakefield, and Isobel, from Durham City.

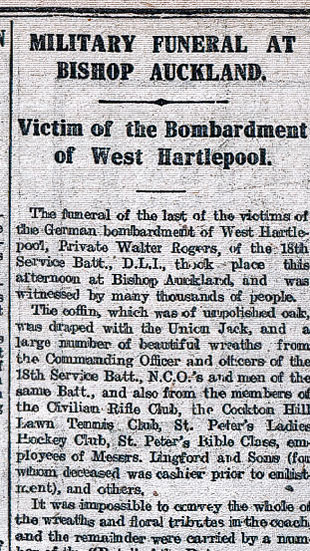

PRINTED TRIBUTES: Cutting from the Northern Despatch newspaper – The Northern Echo’s sister evening newspaper

In the 1891 census, he was living with his two older brothers and one sister in the town centre at 61 Surtees Street; in the 1901 census, they’d been joined by another brother and two more sisters and had moved 100 yards or so to 3 Stranton Street.

The 1911 census found the family living at 6 Beech Grove in the Cockton Hill area – the street is no longer standing.

Pte Roberts’ obituaries say that at the time of his death, he was acting chief clerk at Lingford’s famous baking powder factory in the town.

He was a member of the local photographic society, hockey club, golf club, Cockton Hill Tennis Club, the Civilian Rifle Club and St Peter’s Church choir.

All organisations sent wreaths for the coffin and members for the procession which, said the Despatch, was “at least a mile in length”.

In the cemetery, “the service was conducted by the Rev AE Douglas, formerly vicar of St Peter’s, and at the conclusion, the Last Post was sounded and a volley fired over the grave”.

So Bishop Auckland laid to rest its first victim of the Great War.