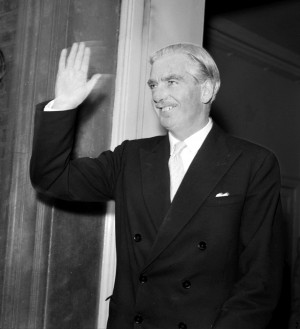

STAUNCH AND WISE ALLY: Reg Park. The photograph of Reg on today’s front cover was taken in France in 1916. Reg’s father appears to have lent the photograph to the Evening Despatch newspaper, which reproduced it alongside a picture of brother Tom on June 10, 1916 – six weeks before Reg was killed

ON July 20, 1916, Captain Anthony Eden, the future Prime Minister, wrote from the First World War trenches to John Park, a grocer’s assistant of High Northgate, Darlington.

“I have a tragic and at the same time a proud duty to perform in telling you all I can about the death of your son, who was killed in action this afternoon,” he began.

It must have been a terrible letter for the 19-year-old Eton-educated officer to compose; it must have been an even worse letter for Mr Park to receive.

The captain continued in pencil: “He was killed instantly and can have suffered no pain whatever.

“Your son was my platoon sergeant and he was absolutely invaluable to me. A truer and a straighter man never walked this earth.”

Eden, writing minutes after he had buried 22-year-old Sergeant Reg Park beneath a little wooden cross, underlined for emphasis the sentence about his dead colleague’s qualities.

“He was more to me than my sergeant,” he wrote. “He was a friend whom I esteemed very highly.

“His loss is absolutely insufferable and I can never have a man who could possibly replace him.”

Sixty years later, after Capt Eden had risen to be Foreign Secretary during the Second World War and Prime Minister during the mid-1950s only to fall over the Suez Crisis, he still referred to Sgt Park as “a staunch and wise ally”.

Eden was born at Windlestone Hall, near Chilton, County Durham, in 1897, into a very conservative landed family. When he was 18 and studying at Eton, he was invited to recruit a platoon of Yeoman Rifles from Durham which he could lead into battle.

One of those who enlisted in September 1915 was ironmonger’s assistant John Reginald Park – “Reg”. He’d been born at Easby, near Richmond, in 1894, but after his mother died in 1904, he’d moved with his family (father, two brothers, two sisters) to 11, High Northgate, Darlington.

HOME STREET: This is the start of High Northgate, Darlington. Although the house numbers have changed unrecognisably today, the Parks’ home of No 11 is probably in view

Late in 1915, Reg, 21, found himself training with the Rifles amid the deer at Duncombe Park, Helmsley, North Yorkshire, under the command of Capt Eden.

Despite their differences of background and age, it is clear that the young Etonian came to admire and rely on the ironmonger.

“Almost my height, but broader and stronger than I, with dark hair and blue eyes and a quick smile, Reg Park could have attracted many girls but was loyal to one,” wrote Eden in his memoirs, which were published before his death in 1977.

“Equable and firm in temper, he took his duties very seriously.”

In fact, Private Park was promoted to be one of Eden’s four platoon sergeants.

By the spring of 1916, the 21st Battalion (Yeoman Rifles) of the King’s Royal Rifles Corps were in northern France. Soon, they were in the thick of the fighting near Ypres, and very quickly, Reg was the last standing of the original four sergeants.

“I have never dreamt that things would be quite as bad, but of course one has not to grumble – it is what almost everybody in the trenches has to put up with,” he wrote in a letter home.

SUEZ CRISIS: Sir Anthony Eden in 1956 when he was Prime Minister at the height of the Suez Crisis

Only a few of Reg’s letters survive, but they show his concern for his men, a trait that impressed Capt Eden.

For example, Reg wrote that Sydney Lonsdale “withstands the bombardments very badly. He seems an awful nervy chap, but I put him in one of the best dugouts in the trench and tried to let him off as easy as possible”.

On July 4, 1916, Reg wrote a graphic letter to his father. Apart from three days in hospital having a couple of rotten teeth pulled out, he’d been under continuous fire at the frontline.

“Just imagine for a moment what it is like to go to bed in a light wood hut but with guns both in front and behind going the whole time. This is when we are out of the trenches, so you can realise what it is like in the trenches. We have been in the front line the whole of the time.

“As you will know by what appears in the papers, we are making headway, but not without the loss of many good men. I have had many narrow goes.

“One night when I was out in no man’s land, which is the ground between ours and their trenches (70 yards), a machine gun was turned on us, but we dropped just in time.

“We had a corporal killed one night whilst putting wire up. We had two more men killed during the few days we were out ‘resting’. They were twin brothers.

“Another awful thing about the trenches is the awful smell caused by graves being blown up with shells. This is continually happening. You will be thinking this is a very pessimistic letter, but there is still one other thing which I detest most of all, and that is a gas attack. There is nothing worse.”

However, he finished his letter: “The men are most wonderfully cheerful and optimistic and are standing their troubles very well indeed. They soon seem to forget about one of their pals being killed, and after a ‘strafe’ they start hunting for nose caps of the German shells.”

The nose caps were sought-after souvenirs to send home.

Those are the last known words of Sgt Park. Sixteen days after writing them, he was killed, about ten miles south of Ypres (in the 1930s, when Eden was Foreign Secretary, he met the German leader Adolf Hitler and they discovered they had probably been in directly opposite trenches near the Belgian town).

The next letter through the door of 11 High Northgate, therefore, was from Capt Eden, written immediately after Reg had been buried.

“All of us here honoured him as a fine brave man beside whom it was an honour to fight, and no nobler life was laid down in this ghastly struggle for king and country,” he said.

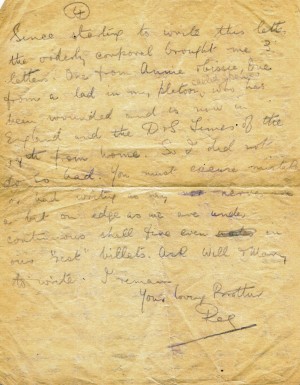

LETTER HOME: One of Reg’s letters from the trenches to his sister Nellie in High Northgate, Darlington

Understandably, Reg’s father took the news very badly and it fell to his 20-year-old sister, Nellie, to break the news to their 19-year-old brother, Tom, who was himself fighting in northern France.

Her letter can be seen on today’s front page. “They all speak very, very highly of him, but that doesn’t make the loss any the less,” she wrote. “Poor dad is in such a way.”

Mr Park appears to have replied to Capt Eden, asking for more information, which came in a letter dated July 29, 1916. Eden said he was first on the scene after the shell struck the dug-out.

“This much is certain, he did not suffer at all. He can have known nothing,” he wrote. “There are only too few men in the world of your son’s stamp, and he has left a memory behind him that will always be cherished by those who had the privilege of his acquaintance.”

However, it was not until his biography was published in 1976 that the then former prime minister described how Reg had died.

“Rats were a plague in the trenches,” he said. “They were very much resented, not least by Reg Park for their greed after rations and the added dirt and discomfort they created for his men.”

So, with Eden’s agreement, Reg had been working in an old fort to rid the platoon’s trench of vermin.

“A 5.9 shell had devastated the fort and Reg had been killed instantly,” wrote Eden. “Reg had chosen this unused fort to set up his rat-traps. He had one rifleman to help him and had just sent him out to get some more wire when the shell came.

“Thus poor Reg had fulfilled the frontline soldier’s philosophy that if somewhere there was a shell with your name on it, it would find you wherever you were.”

As captain, Eden had to censor his men’s letters, and he was struck by how the whole platoon mourned the popular sergeant in writing. “The greediest man among them wrote: ‘We have lost our sergeant. He was a good man and watched out for our interest. Now I suppose the officer will take more of our rations.’ How much Reg would have laughed at that,” he said at the conclusion of his chapter.

At the end of August 1916, the platoon at last left the frontline – and so they left Reg in what is today the Berks Cemetery Extension in Comines-Warneton. As they departed, Capt Eden felt moved to write a last letter to Mr Park describing where Reg lay.

“It is a plain white cross with the single inscription which marks the grave of a brave and faithful soldier,” he wrote in faint pencil. “We can but hope & trust that he is much happier in the world in which he now is.

“I still have one or two small souvenirs of his which I will bring to you when I come on leave.”

It is believed that the next time he was home in Windlestone Hall, Capt Eden kept his word and called on the Parks in 11 High Northgate, to give them the treasures.

With many thanks to Reg Park’s relatives, Margaret North and Dorothy Lincoln. Reg’s brother, Tom, survived the war. The family’s letters are now in the Imperial War Museum.