Joseph Pease in 1914 when he enlisted from Crook

At the start of the Great War, Joseph Pease, great-grandson of South Durham’s first MP, was spoiling for a fight. By the end, he felt ‘soldiering is a waste of life’.

ON October 11, 1914, Joseph Pease wrote to his father: “What the –––– is the matter with the War Office?” Joseph was 25. He was manager of Bowden Close Colliery near Crook, and he was itching to get to “work with the Germans”. His father was Jack, president of the Board of Education in the HH Asquith Government that took Britain into the First World War.

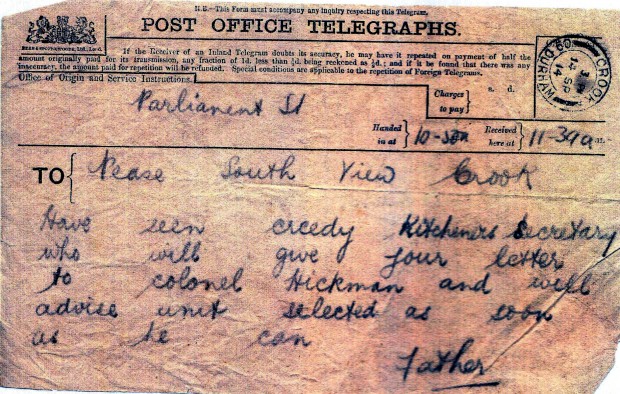

When Jack Pease, who lived at Headlam Hall, near Gainford, was unable to dissuade his son from enlisting, he pulled Parliamentary strings to get Joseph where he wanted to be – Joseph’s call-up papers were signed by Lord Kitchener himself.

Despite this, Joseph’s letters home to Headlam reveal a frustrating war. In Gallipoli, Egypt, Salonika and finally France he had long months of boredom, when there was nothing to do but fox-hunt, duck-shoot and wild-pig-stalk, which were punctuated by brief spells of frantic warfare.

October 28, 1914, from Huntingdon

I wish we were at work with the Germans… I look upon this life as a good holiday. It feels quite strange having no reports to sign and bills to check and lousy Pitmen to quieten.

Joseph left his 1,500 miners at Bowden Close, and his home of South View, in Crook, and was posted to the reserve cavalry in Huntingdonshire.

After a running battle with the War Office, he was transferred to the Lovat Scouts – a Scottish commando unit that specialised in stalking and shooting.

But rather than be sent to the frontline as he craved, the Scouts were despatched to guard the Lincolnshire coast from German assault.

Disillusionment began to creep in to his letters home.

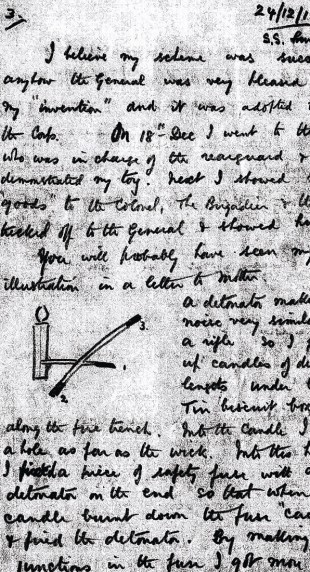

Joseph’s letter of December 20, 1915, telling how he’d fooled the Turks into thinking the British were still in their Gallipoli trenches. Many of his letters included drawings of his inventions – this one shows the candles used to create the sound of rifle-cracks

November 24, 1914, from Huttoft, Lincs

Our efforts appear to me to be practically useless. We have been making trenches and bomb-proof shelters along the coast, and have put up wire entanglements… all of which I imagine would be blown to pieces by a few heavy shells.

After a year of inactivity, Joseph was finally sent to the front.

September 7, 1915, on a train to Devonport

I haven’t a care in the world now except to put up a good fight and leave the rest to Providence. Please don’t worry about me. I shall write whenever I can.

He sailed on SS Andania to the Dardenelles, in the eastern Mediterranean. Joseph witnessed British warships repeatedly bombarding Turkish positions, while he was fighting a medical campaign of his own.

October 14, 1915, from the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force (MEF)

I am back in the trenches again, still a little bit on the loose side, but feeling in good form… Shells and bullet continually whizz past over the parapet. It seems a terrible waste of life, ammunition, and time – I wish I were back at work again instead of playing this stupid game

October 27, 1915, MEF

I have two trench mortars and a catapult with which I fire off bombs at the enemy’s trenches. It’s like a school boy who pulls the front door bell and runs! For no sooner have I fired these toys than a real strafe takes place at my ‘toy’, which I pick up and take away and start off again at another place!

The Turks hurled bombs back at Joseph. He dissected the unexploded ones and discovered that “the devils use Curtis & Harvey’s explosive – same as we use down the pits”.

The Turks drove the MEF backwards, and this provided Joseph with his finest moment. Always inventing things, he created a way of fooling the enemy into thinking that the British positions were occupied long after the British had evacuated. This cunningness allowed the MEF to evacuate safely and gained Joseph a Mention in Despatches.

He explained:

December 20, 1915, MEF

Last night we all vacated Gallipoli… Everything went excellently and we hadn’t a single casualty. Two days previous I produced a scheme for continuing ‘rifle fire’ after we had vacated the trenches. The device was simple – a candle, a piece of safety fuse, and a detonator. The fuse being stuck into the candle & the detonation caused by the candle burning down made a noise similar to the crack of a rifle… Many of these candles were placed under tins along the fire trench down the line & ‘rifle cracks’ continued long after we had left!!

Spending Christmas Day on a Greek island, Joseph provided his family with details he had previously concealed. The weather had been as dangerous an enemy as the Turks, filling the trenches with snowwater which had reduced his squadron of 150 men to just 60. He wrote:

December 25, 1915, from Mudros, Greece

Shells always missed me, although I had two or three narrow shaves. One day I did get a ‘glif’. I was looking down the enemy’s trench through a glass when a bullet cut through the top sandbag and passed horribly near! On Nov 25, we got drowned out of our trenches… The Azmac Dere river came down in torrents, swept away the barricades and flooded down into the trenches. It was damnably cold… Many of the men died on their way back & the hospitals were overflowing 20 fold. It required a hell of an effort to keep oneself going – in peace time I would have thought it impossible, but it’s wonderful what one can do at times…

From Greece, Joseph was shipped back to Cairo, Egypt, where he found 11 Christmas parcels waiting for him. Two were from Darlington and five from Gainford, which contained “chocolate, cigarettes, vaseline, tooth powder, brushes, stockings, handkerchiefs, Edinburgh Rock, soup, Septophon, lice underclothing…”

The Scouts were based in the desert. There was little to do except sight-see pyramids and chase desert foxes. He wrote:

KEY FIGURE: Jack Pease, Joseph’s father, was a member of the Cabinet that took Britain to war

April 16, 1916, from Minia

I haven’t the slightest idea of our motive or how long we are to remain here… What a contrast to the Western Front. It makes one wish one could do something and get a proper move on… I have no toys to play with, no catapults, trench howitzers and grenades with which I can amuse myself. All I’ve got to look after is 30 men, inspect their rifles, clothing and feet daily, and go out for a Sunday walk.

The inaction prompted his father, Jack, to pull a few strings to get him transferred to where he could employ his mining skills. It came to nothing, and so it fell to his mother, Elsie, to cheer him up.

April 23, 1916, from Minia

This peace soldiering doesn’t suit me very well… Your letter of April 13th arrived last night with some illustrated papers from Mother. The old Northern Echo reminded me of the ‘Durham Geordie’ about whom I have heard nothing for so long.

In November, Joseph was sent to Salonika to stop Bulgaria, aided by Germany, from sweeping into Greece, but the war was going against the British.

December 14, 1916, from Salonika

Things are looking pretty black just now… The area Germany covers seems enormous and I am sure we will want an enormous manpower to hold our own on every front.

The perilous situation caused Prime Minister Asquith to be replaced by David Lloyd George. Jack lost his Cabinet job as Postmaster General and was put forward for a peerage.

January 17, 1917, from Salonika

You say you wish to know what title I should like you to take, well I fancy “Teesdale of Headlam” the best… However that’s not of much importance in these peculiar times.

Jack was enobled as Baron Gainford of Headlam, a title Joseph would inherit in 1943. In Salonika, there were long spells where Joseph had nothing to do but shoot the wildlife. Sporadically, though, the war intervened.

February 25, 1917, from Salonika

I set out with a patrol which succeeded in killing 1 Turk and possibly wounding another, but we lost one man. He was hit right through the head and I and two others had a desperate time getting him back. It was bad luck, but it can’t be helped. This country is most treacherous and blind. It contains so many surprises.

Joseph became battle-hardened.

On December 3, he wrote that “Allan Gilmour, who had to have his leg off, is very cheery and looking well”. But on December 17, he reported that “Allan Gilmour, who was shot in the leg on Oct 26 died two days ago, of malaria.

He was getting on so well.

It will be a great blow to his wife”.

The telegram Joseph’s father sent him in Crook showing how he was trying to pull strings with Lord Kitchener to get him to the right place

February 1, 1918, Salonika

Please ask Mother to send me some more cigarettes. I like them so much and smoke so much.

As 1918 drew on, Joseph grew desperate for the war to end, particularly after the death of his cousin, Christopher Pease, the son of Sir Alfred, on the Western Front, in France.

June 18, 1918, Salonika

4 years have nearly passed and I am no ‘forrader’, in fact 8 years backward… Soldiering is a wasted life.

Suddenly there was movement – and hope. Joseph was sent to northern France to begin the push into Germany to win the war.

October 8, 1918, Merlimont

Our chaps up the line have had rather a rough time with shells but were rather pleased when an enemy plane let loose a big bomb into the middle of 50 Hun prisoners and did them all in! They say the Boche morale is completely upset and those in the line…being quite ready to surrender as soon as they can… It looks as if none of the allies are going to accept any such thing as an armistice, nothing but unconditional surrender being of the slightest use.

By November 1918, Joseph’s war had come full circle. He was as desperate to be demobbed as he had been keen to sign up, but once again the slow-moving War Office held him up.

December 29, 1918

This business makes me wild. It is run so badly.

He was demobbed on January 10, 1919. He returned to County Durham to resume his role as a colliery manager.

MAN OF ACTION: 2nd Lieutenant Joseph Pease at Headlam Hall with his younger sister, Faith, in 1916

January 29, 1919, from Headlam Hall

It is very pleasant being free again and every day is a pleasure.

Joseph, the great-grandson of the Joseph Pease whose statue stands in Darlington’s High Row, continued with the family business until the mid- Thirties, when he opened a gun shop in the centre of Darlington.

He sold Headlam Hall in 1943 and retired to a shooting estate in Argylshire, where he died in 1971.

We are indebted to his grandson, Matthew Pease, for lending his letters.