MUNITIONETTES: Girls in the Darlington shell shop in North Road. Picture courtesy of Darlington Centre for Local Studies

THE First World War changed the world for women completely. Suddenly, they were catapulted into factories, into trousers and onto the football field.

This month’s exhibition in the Darlington Centre for Local Studies in the town centre library charts the changes which began following the Shell Scandal of the spring of 1915. The scandal exploded when newspapers discovered that British soldiers fighting in France were short of munitions. The furore caused the Government to form a new Ministry of Munitions, headed by David Lloyd George, and new factories were rapidly opened, staffed almost exclusively by women.

Just as some young men had been eager to volunteer for the Army, as it offered an exciting foreign adventure as opposed to the prospect of a life underground in the coalmine, so many young women were eager to escape the drudgery of domestic service or housewifely duties and contribute directly to the war effort. They made the shells for their men to fire at the enemy.

The Darlington National Projectile Factory went into production in August 1915 staffed by more than 1,000 munitionettes, as the women workers were known. The factory was in the North Road Shops, where Morrisons supermarket is today, and although it was funded by the Government, it was run by the North Eastern Railway, which expected to inherit all the equipment when the war was over.

The shell shop was staffed 24-hours-a-day with the munitionettes overseen by 150 men. They worked eight-hour shifts, with a 30- minute break, for six days a week, mainly producing 18-pounder shells for field guns – they just made the cases, which were then sent elsewhere on the railway to be filled with explosives.

During the course of the war, the women of Darlington made more than 1.5 million shells and repaired more than two million cartridge cases.

But beyond these figures, very little is known about the women’s day-to-day experiences in this new world of industrial work – the library would love to hear from anyone whose ancestors worked in the shell shop and who have left any stories about their war.

We can guess, though, at how a woman’s world changed. She was able to live on her own, or with female friends, near the factory. She could cut her hair short, walk out on her own, take control of machinery, smoke and drink in a pub.

She could even wear masculine clothes. The exhibition contains a February 1917 cutting from the Evening Despatch – The Northern Echo’s former sister paper which was founded during the First World War to bring the latest news from the front to the people of south Durham – which is headlined “Girls in Trousers”, below.

It begins: “One of the conventional revolutions due to the war is the wearing of trousers by women. The demand for these garments for the use of women workers is surprising, says a Liverpool correspondent. They cannot be turned out fast enough.”

The change in fashion, says the article, had been accelerated by a Government ban on the wearing of skirts in workshops – including munitions factories – where there was machinery in motion.

MADE EARLIER: The Darlington shell shop staff, with examples of their work, and Westmoreland Street in the background. Picture courtesy of Darlington Centre for Local Studies. Picture courtesy of Darlington Centre for Local Studies

HAVING got into men’s clothing, women then tried to get into men’s sports. In his recent book The Munitionettes, Patrick Brennan lists 268 women’s matches played in the North-East between December 1916 and May 1919. The munitionette movement started on Tyneside, spread to West Hartlepool and then, before the summer of 1917 was over, had covered all of County Durham.

Sacriston had a team, as did Trimdon. The home ground of the Trimdon Grange Munition Girls seems to have been in Wheatley Hill, although they also played against West Hartlepool women at Durham University’s ground and at Hartlepool United’s Victoria Ground.

Nearly all munitionette matches were charitable events – the Trimdon Girls raised £50 for the DLI Prisoner of War Fund through their game at Durham University. The Northern Echo’s Soldiers and Sailors’ Comforts Fund was another popular cause.

However, not everyone welcomed this advance of the fairer sex. When a match was proposed for Darlington, a letter-writer signing himself “Father of Daughters” thundered in the Evening Despatch: “Is it not time a protest was made against this decadence of womanliness and burlesque of a national game?

“I am the first to admit that women have taken a noble part in the prosecution of the war . . . but it is a different thing when a girl consents to run about before a mixed crowd clad only in knickers and jersey, simply for what amusement she may get out of it. Such conduct is reprehensible.

“It is not enthusiasm for football as a game which has brought these girls’ teams into existence, but the youthful and foolish desire to be daring. Little do they suspect the dangers to which they are exposing themselves, morally and socially.”

The response from the Darlington women footballers was as swift and as deadly as a counter-attack led by Cristiano Ronaldo. They labelled the letter writer “very nasty and impolite” and “narrow-minded and prejudiced”. They pointed out that they worked in trousers in front of men, so why couldn’t they play in trousers in front of men?

“We have taken up men’s work,” wrote A Munition Worker and Footballer, “and there is no reason we should not take up their game.”

And so they did.

SHELL MAKERS: The senior inspection staff at the North Road shell shop, which was at the Westmoreland Street side of the railway works in Darlington. The men on the chairs clearly have the power over the women at their feet, and note the huge pile of shells behind them. Picture courtesy of Darlington Centre for Local Studies

In Darlington, the first recorded women’s match was between Rise Carr Girls (presumably from the rolling mills) and Darlington Railway Athletic at Brinkburn Road. Rise Carr won 3-1, with Sarah Hooper scoring twice.

FOR the next decade, Sarah was the doyen of Darlington’s female footballers. She had the game in her blood – her uncle was the £600 Charlie Roberts, of England and Manchester United fame, and her brothers, Bill and Mark, both played for the Quakers, with Mark going on to become a Sheffield United legend.

The second recorded match was a week later, on October 6, 1917, at Feethams. It was between the NER Munitions Girls and a team of wounded soldiers who were recuperating in the Voluntary Aid Detachment hospital at Woodside, off Coniscliffe Road (see Memories 173).

“The soldiers played with their hands behind them, but even so were rather too good for the girls, who, however, put up a pretty good show and were only beaten by a goal margin in the end,” reported the Echo. The score was 7-6, and the match raised £20 for the comforts fund.

Other reports in that day’s Echo included news from the Brewery Field, Spennymoor, where the Trimdon Munitionettes had taken on Hartlepool Shippers’ Union. “The game, which was most exciting, ended in a draw of one goal each,” said the Echo, and Miss Leggett was named as the scorer of Trimdon’s penalty.

The paper also contained the draw for the first round of the Tyne, Wear and Tees Munition Girls’ Cup – which is believed to be the first female football tournament ever organised in Britain. There were 14 teams in the Tyneside section of the draw and the Teesside section included four from Middlesbrough, three from Darlington and two from Skinningrove, as well as the Trimdon Girls. Teams, though, were very fluid, and there were lots of drop-outs, name changes and nine-a-side matches. But of the Darlington teams, Rise Carr, led by the free-scoring Sarah Hooper, reached the semi-final where they lost 1-0 to Bolckow Vaughan, of Middlesbrough. The ironmasters’ girls, though, lost the final at Ayresome Park 5-0 to Blyth Spartans on May 18, 1918.

A second Munitionettes Cup was planned for 1918-19, but peace intervened and it fizzled out as the munitions factories closed. But the world for women had changed forever.

The library’s exhibition runs until the end of February. Many thanks to Mandy Fay and Katherine Williamson for their help

MATCH REPORT

November 17, 1917, at Feethams, Darlington

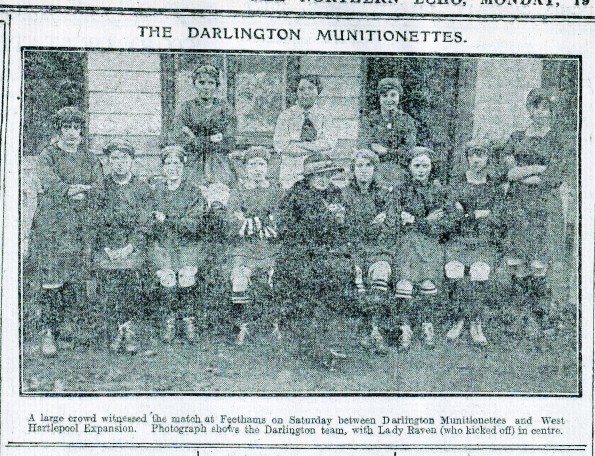

RARE PHOTO: The Darlington Munitionettes, with Lady Raven in the centre, from The Northern Echo of November 19, 1917

DARLINGTON MUNITIONETTES 0 WEST HARTLEPOOL EXPANSION 2

In front of “the largest crowd which has been seen at Feethams for a considerable time”, Lady Raven kicked off. This was typical of munitionettes football where a local celebrity – her ladyship was the wife of Sir Vincent Raven, the NER chief mechanical engineer – started a match (she also presented a pound note for the comforts fund).

In a quiet first half, the Expanded Metal Company – known as Expansion – took the lead through Jessie Spencely. “Johnson, Darlington custodian, caught the ball and should have saved the situation, but instead of getting it away, she dropped it in goal,” said the Echo. Its match report contains the only known picture of the Darlington Munitionettes.

The home girls pressed after the break, but “Sarah Hooper, the redoubtable centre forward, did not have much chance to show her mettle”. H Agar doubled the visitors’ lead with “a fine run up the centre”.

The crowd, said the Echo, had been “treated to an amusing and at times exciting game of football”.

THE WINNERS: The Expanded Metal Company of West Hartlepool team – known as Expansion – who played at Feethams