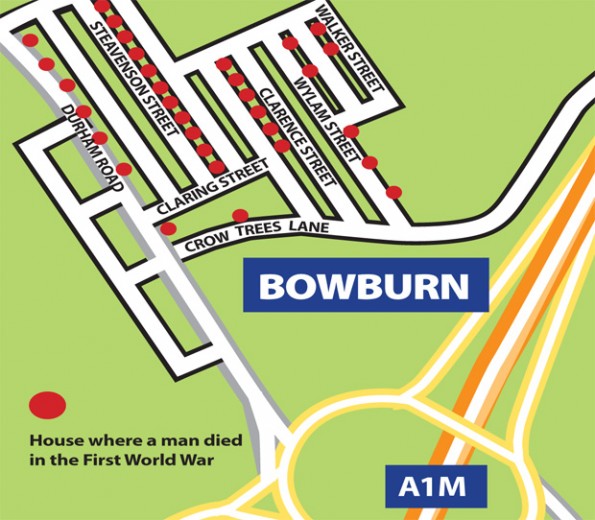

TRAGIC HISTORY: Clarence Street, in Bowburn, today

The sacrifice of war was felt most keenly in Bowburn, a community of 200 homes of which 47 endured the pain of losing a loved one.

CLARENCE Street – an ordinary terraced street, in an ordinary pit village, but one which paid an extraordinary price during the First World War.

At the outbreak of war, there were just 200 pit houses in Bowburn, crammed into five terraced streets packed tight around the colliery. By the end those homes had lost 47 dead: 47 fathers, brothers and sons who would never return; 47 families touched by tragedy.

It was a village born in hope just eight years before the war, but by Armistice Day Bowburn was a village of widows and spinsters, living in streets where all the young men were dead.

Clarence Street lost six men, three killed in a single day of slaughter, and stands as a bricks-and-mortar symbol of the suffering endured by the families of Durham Coalfield.

COAL has been mined from beneath Bowburn for generations, but the village wasn’t founded until 1906 when the Bell Brothers coal company sunk the shaft of their new colliery, the first sod cut by the daughter of the company chairman, the exotic Gertrude Bell, explorer, Islamist and spy. The company built 200 houses in five terraces: Durham Road, Steavenson Street, Wylam Street, Walker Street and Clarence Street.

The houses which went with the job were brand new and three-bedroomed, a rarity in a coalfield of two up, two downs. This was a town literally built on coal: clay taken from the pit was turned into bricks for the houses.

Soon enough there were two churches, a school, a couple of police houses and a workingmen’s club, but otherwise the village functioned solely to supply the mine with miners and into this boom town flowed families from across Durham, young families full of hope and expectation of a new start in a better place.

AMONG the first arrivals were John Charles McKeown and his wife Frances Elizabeth, with their five children. Born in Ireland, the couple had moved to County Durham where John worked as a miner in Shincliffe, before taking his young family to the infant Bowburn.

The family moved into 22 Clarence Street, including their son James , also a miner, and teenage daughter Mary Elizabeth, known to all as Eliza. Next door to them at 23 Clarence Street lived Jackie Hunter, a young miner from Sherburn Hill, who moved to Bowburn to marry his sweetheart, Mary Elizabeth Thornton. Out the back of the McKeowns, across the narrow alley which separated their house from 20 Wylam Street, lived Robert Bell, who was 27 in 1914 and married with three children.

Michael Joseph Lowery

The McKeowns had not been there long when Michael Joseph Lowery came into their lives.

Born in Sligo, he too followed the itinerant life of a miner’s son. In 1901, aged eight, he was living at Hutton Henry and ten years later he was at Wheatley Hill, working down the mine with his father, John. He followed the work to Bowburn where he met and fell in love with Eliza McKeown. The couple were married in 1915 and Michael, who signed his letters Mick, moved in with his in-laws at 22 Clarence Street.

WHEN war was declared, the workingmen’s club did its bit by voting to shut its doors at 9pm for the duration, while a local fundraising drive to buy Christmas presents for servicemen raised £43 2s and 8d, including more than £13 through house-to-house collections.

Just weeks after war was declared, Bowburn-born Able Seaman George Winwood, torpedo operator on HMS Arethusa, was killed during the Battle of Heligoland Bight, as a flotilla of British destroyers tried to force German cruisers into the open sea.

His funeral was held on Wednesday, September 2, at St Saviour’s Church, in Shotton Colliery, where the 23-year-old had been a member of the choir and the Young Men’s Bible Class. Crowds lined the streets as his coffin, draped in the Union Flag, was led in procession by the Shotton Colliery Silver Band and flanked by a firing party from the Northumberland Hussars.

The following Monday, 20 men from Bowburn marched in formation from the village to the recruiting office at Coxhoe Literary Institute to sign up.

JAMES McKeown, his brother-in-law Michael Lowery and next-door neighbour Jackie Hunter all signed up with the 25th Battalion of the Northumberland Fusiliers, better known as the Tyneside Irish Battalion – despite its name, around three-quarters of the battalion was recruited from County Durham.

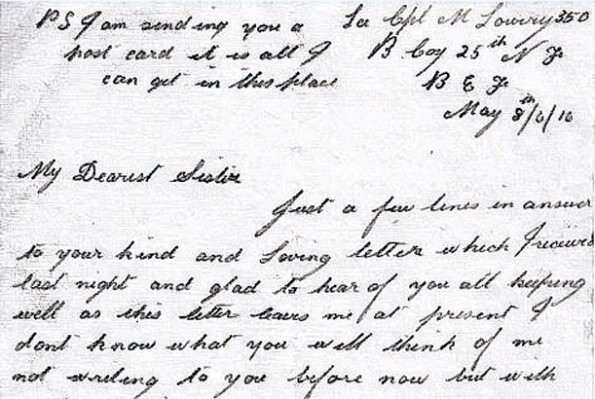

After basic training, they were despatched to France early in 1916, which meant Michael missed the birth of his first child in March, named Michael after him. On May 8, 1916, Michael wrote home to his sister Sarah: “You think I will get a surprise when I come home and see that little son of ours. Eliza tells me he is the picture of health but it’s to be hoped it won’t be long now before I get home to see him and you all. It will be a big day when we all get home for good. I wish the time was here now and I’ll bet you are all wishing the same. But we will wait till it is God’s will to end this war.”

LETTERS HOME: Michael Lowery’s letter home to his sister, Sarah, on May 8, 1916

He added: “I wish I could get leave to see him, but I don’t think we will be long now before we are in the trenches. We are just a short distance behind the firing line and you can hear the guns going off and I can tell you that it isn’t very pleasant to hear them.”

The Tyneside Irish were part of a simple plan. After an eight-day bombardment, which would blow the German trenches and wire to smithereens, enormous mines would be detonated beneath the enemy positions. Then the British would walk unopposed across no-man’s-land…

The Northumberland Fusiliers were formed up on Tara and Usna hills, about a mile behind the British lines. Down the slope ahead of them lay the front, then no-man’s-land and the German occupied village of La Boiselle. When the mines exploded, the 10th Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment, better known as the Grimsby Chums, would capture the crater and mop up what resistance survived. Then the Tyneside Irish would stroll down the road towards the village of Contalmaison, an advance of about five miles, with rifles sloped over their shoulders…

MISSING IN ACTION: James McKeown

THERE wasn’t a cloud in the sky on July 1, 1916, which dawned with the promise of a beautiful summer’s day to come. As the bombardment lifted, Mick Lowery and James McKeown were lined up on the left of the Albert to Bapaume road. About 50 yards to their right was Jackie Hunter, standing near his friend, Sgt Wild, close enough to see each other if they had looked along the line.

At 7.28am, the Lochnagar mine was detonated and an unknown number of young German soldiers was vaporised by 60,000lb of explosives. The whistles sounded and the Grimsby Chums went over the top. The German wire and trenches, though, were intact, and when the German machine gun teams heard the whistles, they emerged from their trenches and took up their positions which commanded a perfect field of fire across the whole valley. They slaughtered everyone who entering the killing zone – it was said their guns glowed white hot and they were forced to urinate on them to keep them firing.

From their vantage point on the hillside, the Bowburn lads watched the massacre of the Grimsby Chums. Then the whistles blew once more, and this time they were sent to their deaths. By all accounts, not one soldier flinched.

Their objective was to reach five miles; most didn’t make it to the British frontline. Among the 2,100 men of the Tyneside Irish lost that day were Michael Lowery and James McKeown. Their bodies were never found and they remain out there, somewhere in the fields of Flanders. Both were aged 24. Eliza lost her husband and her brother in that one day: she had been married, become a mother and was widowed in just one year.

Some days later, Jackie Hunter’s widow, Mary Elizabeth, received a letter from Sgt Wild.

He wrote: “We got to their second line and the Germans gave us lots of machine gun fire and I got to within about 20 yards of a German machine gun.

“A bullet went through my hip and another through my arm.

“Jackie dragged me about ten yards to a shell hole and just as he pushed me into the safety of the hole, he was shot through the head.

“A shrapnel shell, bursting overhead, lodged a piece of shrapnel in me, but I managed to crawl into the hole.

“I was there about 16 hours and all the while a lovely sun was burning down. Poor Jackie and I lay all that long burning day together in that shellhole.

“You can imagine my feelings, lying there with one of my best chums who’d given his life to save mine.”

Robert Bell, whose house backed onto the McKeowns’ home, was killed that same day: four men, who lived in three adjacent houses, killed alongside each other.

LEFT BEHIND: Eliza and Michael Lowery junior, the son his father never saw, outside their home in Clarence Street shortly after the end of the war

THEY would not be the last. In all, Clarence Street lost six men killed. William Harrington at No 19 survived being wounded twice, died at the age of 22 just three months after the opening day of The Battle of the Somme.

Sailor John Gilligan, at No 10, survived the horrors of Gallipoli, but was drowned when his ship went down in a North Sea gale in February 1918.

The youngest of them was 19-year-old Thomas Ramshaw, who lived with his parents at No 25. He died of his wounds in September 1918 just two months before the end of the war.

Their names are carved on memorials in honour of their sacrifice, but there are no plinths for the families they left behind.

There are unconfirmed reports that some of the village widows were thrown out of their pit houses, which were reassigned to working miners, and sought refuge in the tents at Peat Edge, a temporary camp on the edge of the village.

It was said that by the end of the war, traumatised postmen were refusing to deliver War Office telegrams, instead sending out schoolboys to break the black-edged news to the recently widowed.

One hundred years on, firefighter Michael Burdon has launched a campaign to fix a simple bronze poppy on each of the 47 homes in Bowburn which lost someone during the Great War. It is a belated tribute to the extraordinary sacrifice endured by an ordinary pit village.