MEN AND MUD: Helping a wounded comrade at Passchendaele in the late summer of 1917

ONE hundred years ago, the telegram boys in the North-East were beginning one of their busiest periods of the First World War, delivering dreadful news to the families of young men out fighting in Flanders fields.

The slaughter that was the Battle of Passchendaele began 100 years ago last Monday – “the biggest battle on the Western Front”, as The Northern Echo’s headline of the day called it, and you will undoubtedly have seen the royal commemorations of the anniversary.

One of the first sent over the top by the buglers at 3.50am on July 31, 1917, was the Wearside battalion of the Durham Light Infantry. They were launched in 36 hours of fierce fighting in which they lost 431 men, either killed or wounded.

So intense was the barrage the enemy threw at them that they had to communicate with their headquarters by carrier pigeon, because human runners did not survive to tell the tale or to request the desperately needed reinforcements.

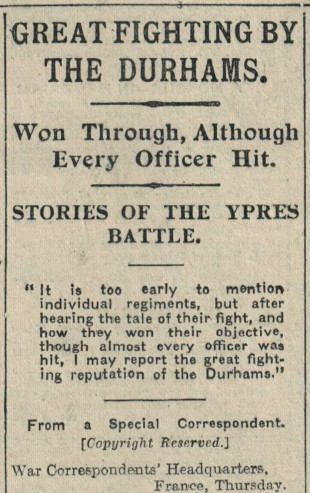

BRAVE MEN: From The Northern Echo of August 3, 1917

So brave were the Durham Pals of Wearside that they came to national notice immediately.

“It is too early to mention individual regiments, but after hearing the tale of their fight and how they won their objective, though almost every officer was hit, I may report the great fighting reputation of the Durhams,” said The Times newspaper’s special correspondent.

The Durhams, he said, had come up against “a difficult task in reducing a nest of dugouts in front of the main line of the advance” – a line of heavily armed German pillboxes. But the men pushed through. It was, he said, “a dashing piece of work, admirably done”

And the stories of the officers of the 20th DLI are remarkable.

One of the first to fall was Captain Fawcett Wayman, 21, of Sunderland, whose death the Echo reported on August 11, 1917. It said he had already been twice wounded on the Somme, where he was awarded the Military Cross for gallantry. On July 31, he was wounded before zero hero – the 20th lost 100 men in the pre-battle hostilities – but resumed his place in the frontline until he was taken down by a shell. His body was never recovered so his name is recorded on the Menin Gate in Ypres.

HEAD WOUND: Sgt TM Fletcher, killed at the Battle of Passchendaele. Picture courtesy of the Durham County Record Office

Then there was Lt Thomas Fletcher, 28, of Highfield, Chester-le-Street, who won the Military Cross that day “for conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty,” according to the citation. It tells how he was wounded before zero hour, but returned to the fray with his head bandaged to lead his men in the attack.

“This he did with great gallantry until wounded a second time, gaining both objectives and setting a splendid example of fearlessness and energy to his men,” finishes the citation.

That second wound took his life, and his body disappeared into the mud as the rain set in at lunchtime, so he, too, is recorded on the Menin Gate.

And, of course, it is the callousness of the weather as much as the brutality of the fighting that makes Passchendaele so unforgettable. At the end of the first couple of days’ fighting, the Darlington & Stockton Times’ man at the frontline reported: “When I say that the weather since midday has become worse than it has yet been this week and that the whole of the battle area is a veritable quagmire, I think I have about exhausted the current news. One shirks even contemplating what existence is like in the lagoons and brimming rivulets which were once shell craters and trenches.”

This was once-in-a-century rain where men were slowly sucked down to drown in the mud, unable to haul themselves out, screaming at the inevitability of their end.

So perhaps those members of the 20th DLI were lucky. They were shattered by the first 36 hours of fighting and when dusk fell on August 1, 1917, they were relieved and fell back.

They did return to the frontline at Passchendaele during September, where they were joined by the 10th, 11th and 12th battalions, and although they all suffered further losses, none were quite so graphic and wholesale as those of the opening hours.

HUMAN REMAINS: The wreckage of a tank beside a shell crater on the Passchendaele battlefield

THERE can be barely a North-East town, or village, that was untouched by the slaughter of Passchendaele.

For instance, Darlington: Lt William Walton of Elton Parade was one of the officers of the 20th DLI who was killed on July 31, 1917, and his body was never recovered.

According to the magnificent database, compiled by historian Stephen Nicholson, on The Northern Echo’s North-East at War website, he was one of six men from the town to die on that opening day.

Well, “men” is an exaggeration, because 15-year-old Pte John Cockfield went over the top at 3.50am that day and never came home. John lived at 40, Havelock Street on Albert Hill, and was the only son of Ellen and Joseph, a saw setter in a steelworks. He was in the 2nd Yorkshire Regiment and perished at Pilkem Ridge, to the north of Ypres.

He is the youngest known Darlingtonian to die in the First World War, and he is buried in the Tyne Cot cemetery which was the focus of the commemorations. Does anyone know any more about him?

- The only other known 15-year-old from Darlington to die in the First World War was Bugler George Sanderson, of 38, Dodds Street. Like Pte Cockfield, he was in the Yorkshire Regiment, but he died of fever in Walkergate Hospital in Newcastle without making it overseas.

KNOWN UNTO GOD: British graves at Tyne Cot cemetery near Ypres

HAVING named two of the Darlington six to die on the first day of Passchendaele, it would be invidious not to mention the other four. They were:

Pte Percy Doncaster, 35, of Beech House in The Mead. Before he joined the Coldstream Guards, he was a travelling salesman with the Nottingham chemists, Newball & Mason, and a noted organist at Bondgate Methodist Church;

Pte William Horton, 21, of 9 Dickinson Street. He was in the machine Gun Corps but had worked as a locomotive cleaner for the North Eastern Railway;

Lt Richard Johnson, 23, of 101 Stanhope Road. The Northern Echo reported his death on August 6, 1917, saying that he was a Darlington Grammar School old boy who’d left his agriculture studies at Edinburgh University to join the DLI when war broke out. He’d been invalided home during the Battle of the Somme in 1916, but in May 1917 had been fit enough to join the Royal Engineers. The Echo said that his parents in No 101 had received a letter from a wounded officer telling them that “their son’s death was instantaneous and that he was instrumental in saving the lives of several of his comrades”;

Pte Ernest Siddle, 27, of 12 Barningham Street. He was a plater’s helper at Cleveland Bridge, but had left his three younger brothers and sister to join the Grenadier Guards.

CENTENARY REMEMBERED: The Duchess of Cambridge lays flowers at the grave of the unknown soldier at Tyne Cot cemetery at Ypres

THE commemorations of Passchendaele caused Stan Cartwright, 89, of West Auckland, to think once again of his step-brother-in-law, Wilfred Ibitson, who died 24 years ago.

“He was born after his father, John George, went away to fight, and as he was gassed and killed at Passchendaele, the lad never saw his dad,” says Stan.

John George Ibitson, of Union Street, Darlington – the derelict church behind Boots the chemist on Northgate is all that remains of Union Street – was a machine labourer at Summersons’ foundry who married Sarah in 1912. Their only child, Wilfred, was born on June 2, 1914, by which time his father was in the 10th DLI.

BRIMMING RIVULETS: The Passchendaele battlefield in which the 20th Durham Light Infantry was fighting 100 years ago

The 10th joined the Battle of Passchendaele on August 20, 1917, and made such progress that they captured a chateau and 50 prisoners. Sadly, not many of the captives nor the capturers made it back to the British lines as, in the confusion of battle, they were all hit by someone’s shellfire and killed.

The rest of the 10th holed up fairly quietly in Inverness Copse until 4.30am on August 23 when they were reinforced by some British tanks. The tanks, though, immediately became the target of German guns. One tank became disorientated and began firing on the Durhams, wounding two. Perhaps fortunately, the tank was hit twice by German shells and disabled before it could do any more damage to the DLI.

When the 10th was relieved on August 25, it had lost 14 of its 20 officers and 355 of its 608 men. One of those killed on August 23 had been Pte Ibitson, which left his son in Union Street with no memory of his father.

Pte Ibitson’s widow, Sarah, remarried and when her daughter, Marjorie, was born, she became Wilfred’s stepsister. Stan married Marjorie, and Wilfred served in the RAF during the Second World War before settling in Newark.