DIRECT HIT: Cleveland Road in West Hartlepool

THE Headland at Hartlepool is an exposed place, jutting defiantly into the biting wind blowing off the North Sea.

There are long views through white-capped waves down south to Saltburn and up north to Seaham, but today the binoculars chained to the viewing area in the Heugh lighthouse pick up nothing more threatening than a flotilla of turbines on the water, and a squadron of seagulls trying to land with wings outstretched in the crosswind on the green.

But 100 years ago, on December 16, 1914, it was very different. At 8am, from just about the direction of the turbines, three German battleships appeared out of the mist, and opened fire.

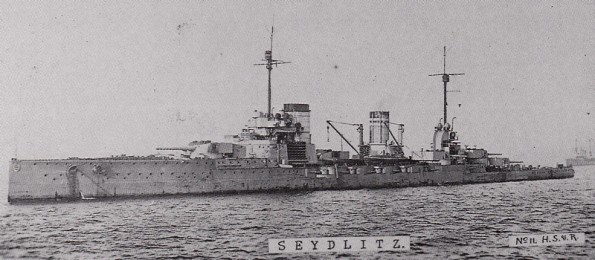

The first shell from the flagship battlecruiser Seydlitz, landed beside the Heugh battery on the Headland and killed four Durham Pals outright.

They were from the 18th (Service) Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry, volunteers who had responded to the call by Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, to form “pals” regiments – groups of friends who all joined up together. In alphabetical order, they were Privates Charles Clark and Theophilis Jones, both of West Hartlepool; Corporal Alix Liddle, of Darlington, and Private Leslie Turner, of Newcastle.

SHELL SHOCK: Three Hartlepudlians hold one of the smaller, unexploded shells fired from the German warships

The Ministry of War, fighting the propaganda war, decided that Pte Jones, 29, was officially the first soldier to die, perhaps because he was an assistant headteacher in West Hartlepool and only the callous Hun would chose to wipe out such a valuable and honourable man on his own soil. A plaque now marks the spot where he fell.

More likely, the truth is that all four, including the colliery clerk from Darlington, died simultaneously – the first people to die on the mainland in this terrible war.

Naturally, their fellow soldiers came rushing out of the lighthouse to see if they could help. Seydlitz fired immediately again with the same deadly result. This time Private Walter Rogers, 25, from Bishop Auckland, was among those struck.

“He was killed while in the act of covering up Cpl Liddle, who was cut up with one of the first shells,” said the Northern Despatch newspaper. “Pte Rogers received the full force of another splinter from a shell in the chest, but he lingered for three hours.”

Amazingly, at the same moment about 40 miles down the coast, the same horror was being visited on Scarborough.

At 8am, Lawrence Reeve sat down to breakfast with his wife, Martha, and their four children. He was second-in-command of the War Signal Station at Castle Hill, and had just finished an uneventful night duty.

But the peace of his quiet meal was shattered when one of his men burst into his house and blurted out: “There are some strange ships in sight, but we can’t make out what they are…” The rest of his sentence was lost as the first shells hit, fired from three more German warships which had stolen unseen through the veil of mist into Scarborough Bay.

Their first target was the imposing facade of The Royal Hotel, which they hit with 35 shells. The Royal Suite was badly damaged and the restaurant ruined – the only item that survived was a decanter of wine which a Daily Mirror reporter later sampled in the name of investigative journalism.

For 25 minutes, the Derfflinger and the Von der Tann pounded the town with their 5.9 inch guns while the Kolberg laid 100 mines to the south (those mines are still being washed ashore). Eighty were injured, and 18 were killed, the youngest of whom was 14-month-old John Ryalls, who took ten minutes to die from his brain injury. This caused Winston Churchill to emotively denounce the German “babykillers of Scarborough”.

ABBEY ATTACKED: The Lodge at Whitby Abbey was hit a few minutes after the warships finished with Scarborough

Once they had finished in the bay, the Derfflinger and the Von der Tann sailed a little north and turned their terror on Whitby, bombarding the abbey area with 150 shells. Three people were killed, although here there was a happier story. The thunderous explosions and the fear of imminent invasion caused Mrs Griffin to go into labour and her ten-and-a-half pound baby was born as the shells fell. She named him George Shrapnel Griffin.

Shortly after nine o’clock, after 11 minutes of bombardment, the warships slipped back into the mist.

Up at Hartlepool, people were starting to count the cost. It had been under fire for 52 minutes, with more than 1,500 shells hitting the Headland. Of the 123 people who died, 23 had been killed in their own homes. Thirty-seven were children on their way to school, but most of the victims had been stricken by panic and had rushed into the streets where there was no protection.

BOMB DAMAGE: Rugby Terrace, West Hartlepool, after it was hit by shells on December 16, 1914

Seven churches, five hotels and 300 houses were destroyed or damaged. But the cruellest blow to the Hartlepudlians was that their three gasometers were destroyed – that night they had to sit amid their ruins of their homes by candlelight.

Almost as soon as the warships had disappeared into the mist, the recriminations began. How had they been allowed to come so close, unobserved and unchallenged? What was the Navy up to? The Admiralty response was unfeeling in its abruptness. A spokesman said: “Open towns on the East Coast must expect to be bombarded and we cannot help it. Those who are killed must be killed and their relatives who mourn must mourn. We are sorry, but this cannot be prevented… We cannot scatter our big ships about to prevent bombardments which, though deplorable, are devoid of military significance.”

The Germans were jubilant, rejoicing in their easy victory and taunting the “English rats” for fearing to come out of their holes.

But The Northern Echo said: “This is not war. It is the work of men whose lust for destruction seems only to be limited by fear of the consequences of being caught.”

THE FIRST OF THE FALLEN: Some of the Hartlepool victims, from The Northern Echo

The noise from the bombardment had roared as far inland as Middleton-in-Teesdale. In Bishop Auckland, they thought it was a colliery explosion – until about 10am when cartloads of Hartlepudlians arrived, fleeing what they feared were the first blows of an invasion.

England was now very afraid. Two days later, a wild rumour ran through Hartlepool that a Zeppelin airship was on its way to bomb it, causing a stampede to the station. The coroner, JH Bell, travelling by train to open the inquests into the victims, was delayed by an hour in Stockton because so many frightened people were fleeing the town.

When he eventually arrived, he began his proceedings by saying: “It is perfect nonsense to suppose that this island is going to melt away at the first sound of a trumpet from the other side of the water… I should like to think that the old town will keep its own pluck all the way through.”

So Britain was rocked – but it was also roused. As the Echo said: “The wanton, profitless, and deliberate slaughter of women and children has roused a spirit of determination to resist the designs of an apparently ruthless enemy.”

GERMAN FLAGSHIP: Seydlitz, which led the attack on Hartlepool

The Ministry of War’s propaganda machine used the incident as a call to arms. A poster published a day later said: “The wholesale murder of innocent women and children demands vengeance. Men of England, the innocent victims of German brutality call upon you to avenge them. Show the German barbarians that Britain’s shores cannot be bombarded with impunity.”

The British people lost their indifference to what they had thought was a faraway war which would be over by Christmas, and there was a sudden rush to the recruiting offices.

But for all the change in the national mindset, the dead of the bombardment still had to be buried. At Bishop Auckland on December 21, 1914, as Pte Rogers was laid to rest, his unpolished oak coffin, wrapped in a Union flag, led a procession more than a mile long through the streets, crowded with thousands of people, to the town cemetery.

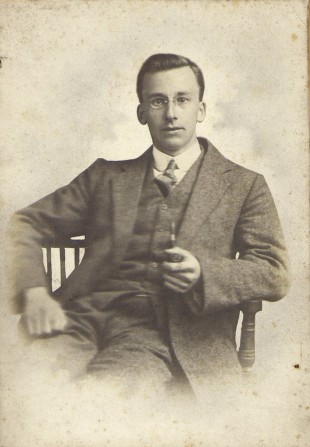

EARLY CASUALTY: Lance Corporal Alix Oliffe Liddle of the Darlington Pals – one of the first British soldiers to die in the First World War

Darlington had laid its victim, Cpl Liddle, to rest the day before amid similar scenes. He lived with Clara, his wife of only seven months, in Sylvan Grove, so his coffin, pulled by two black horses, did not have far to go to West Cemetery.

Behind the hearse came Hoggett’s Military Band, playing Beethoven’s Funeral March, followed by the Pals, their arms reversed in respect.

Said the Echo: “The scene at the graveside was an impressive one. The troops had been drawn up surrounding the grave in the form of a square, with the firing party at one side, and the bugle band at the head of the grave. The mourners gathered around the grave inside the square, while thousands of people gathered in a great crowd outside the military and stood, many of the men reverently uncovered, while the last rites were being performed.

“Immediately the Reverend Francis Peacock had concluded the service, the firing party fired three volleys over the grave into the air, and then from the bugle band came the strains of the Last Post.”

The Echo concluded its account by saying: “Thus was laid to rest the first of the Darlington Pals to give his life for his King and country.”

Despite having their eyes opened by the bombardment of the east coast, no one can have conceived how much more carnage lay ahead for King and country in the next four years.