, 66, and Laura Wilkinson, 12, both of Turnbull Street, West Hartlepool, who were killed in the bombardment

Lawrence Reeve sat down to breakfast with his wife Martha and their four children. It was 8am. Lawrence was second-in-command of the War Signal Station at Castle Hill, Scarborough, and had just finished his night duty.

It had probably been uneventful. It was 1914 and there was a faraway war on. Most people still thought that it would be over – successfully – by Christmas and some local young men had joined up with the scent of foreign adventure in their nostrils.

Then Warrant Officer Reeve’s quiet breakfast – and the country’s calm indifference – was rudely shattered. One of his men burst into his house: “There are some strange ships in sight,” blurted the soldier, “but we can’t make out what they are…” The rest of his sentence was lost as the first shell hit the town. Scarborough was under attack from three German warships which had stolen unseen through a veil of mist into the Bay.

And Scarborough was not alone. At precisely the same time, 50 miles up the coast, Hartlepool was under attack from three more warships. At the Heugh Battery near the promenade, Private Theophilis Jones of the Durham Light Infantry died in the first shell blast – the first British soldier to be killed on British soil by enemy action in what was to become known as “the Great War”.

For the next 70 minutes, the six warships wreaked unimaginable terror on a coast which had seen nothing like it since the Viking raids 1,000 years earlier. The raids had been planned by Admiral von Ingenohl and Kaiser Wilhelm to raise morale within the German navy. It was also hoped that the action would draw a portion of the British Navy into a winnable sea battle, and that it would remind the British that they were vulnerable in their beds in their homes. Perhaps it would even frighten the British into not reinforcing the Western Front with 100,000 recruits in Kitchener’s New Army as it would show they were needed at home.

British spies winkled out a few details of the von Ingenohl plan and at midnight on December 15, Hartlepool received a cable that something was afoot.

No one took it too seriously until, at 7.50am, a routine patrol by British warships spotted the Blcher, the Seydlitz and the Moltke looming out of the mist. The British boats came under fire and withdrew, leaving Hartlepool undefended apart from its two shore batteries.

Down at Scarborough, there were no defences and no warning – until Warrant Officer Reeve had his breakfast interrupted. For 25 minutes the Derfflinger and the Von der Tann pounded the town with their 5.9 inch guns while the Kolberg laid 100 mines to the south (those mines are still being washed ashore).

Sailing south across Scarborough Bay, the warships’ first target was the imposing facade of The Royal Hotel, which they hit with 35 shells. The Royal Suite was badly damaged and the restaurant ruined – the only item that survived was a decanter of wine which a Daily Mirror reporter later sampled in the name of investigative journalism.

This first pass caused Scarborough’s first casualties. Leonard Ellis, 49, was killed when opening up Hunt’s chemist shop in South Street. On the Esplanade, John Duffield dashed to a phone to raise the alarm, followed by his wife. As he pleaded with her to return, a shell landed on top of her, killing her outright before his eyes. “For days afterwards her innocent blood stained the steps and pavement as a reminder of the horrific event,” says a new book on the event.

Having reached the south of the town, the warships turned around. “Each battleship now altered the elevation of its guns and deliberately targeted different areas of the town,” says Mark Marsay in Bombardment! The Day the East Coast Bled. “The bombardment suffered so far was as nothing compared to the hail of shells that now fell. Steel, shell, high explosive and shrapnel rained down over the most populated parts of the town.

“Death and destruction was visited on Scarborough with all the ferocity of hell, the dogs of war let loose to run rampant through her desperate streets.” The carnage was indiscriminate: a couple of postmen delivering letters were killed, one blown 20 yards by the force of the blast. John Ryalls, at 14-months-old, was the youngest victim. “His injuries extensive, especially to his head which was laid open exposing his brain, he died in absolute agony some ten minutes later cradled in the arms of his distraught father,” says Marsay.

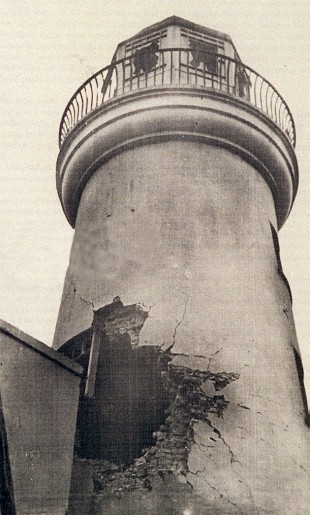

The last shell scored a direct hit on the lighthouse, passing straight through the tower. And then, at 8.25am, the warships disappeared, leaving 18 dead, more than 80 injured and the town in a state of unbridled panic – people dashed to the railway station, saddled up their horses, crammed into their cars in a bid to escape the feared invasion. Several Post Offices ran out of money as anxious folk withdrew their life savings before fleeing.

While the air was clearing in Scarborough, it was still thick with shells in Hartlepool. The Seydlitz didn’t fire its last salvo until 8:52am. Then it too slipped back into the mist with several of its crew dying from wounds inflicted by the shore batteries.

But on the shore, 112 lay dead. Just 23 of them had died in their homes. Thirty-seven were children on their way to school, but many had been stricken by panic and rushed into the streets where there was no protection.

Scarborough lighthouse showing bomb damage

Seven churches, five hotels and 300 houses were destroyed or damaged. But the cruellest blow to the Hartlepudlians was that their three gasometers were destroyed – that night they had to sit amid their ruins of their homes by candlelight.

But even as the air in Hartlepool was clearing, Whitby was coming under attack. At 9am, the Derfflinger and the Von der Tann opened fire and in 11 minutes 150 shells rained down. Three people were killed although here there was a happier story. The thunderous explosions and the fear of imminent invasion caused Mrs Griffin to go into labour and her ten-and-a-half pound baby was born during the bombardment. She named him George Shrapnel Griffin.

At 9.11am, the warships left the North-East coast, and the recriminations began. How had they been allowed to come so close, unobserved and unchallenged? What was the Navy up to? The Admiralty response was unfeeling in its abruptness. A spokesman said: “Open towns on the East coast must expect to be bombarded and we cannot help it. Those who are killed must be killed and their relatives who mourn must mourn. We are sorry, but this cannot be prevented… We cannot scatter our big ships about to prevent bombardments which, though deplorable, are devoid of military significance.” The Northern Echo more or less agreed. “This is not war,” it opined. “It is the work of men whose lust for destruction seems only to be limited by fear of the consequences of being caught.” The German press took a different view. “Only a few months have gone since Winston Churchill spoke those proud words about ‘fetching German rats out of their water holes’,” crowed the Nurnberger Zeitung. “Well, the ‘rats’ have come out when it suits them best. In a short time, we have managed to cause more damage than the English have in the whole sea war up to now.

“It is time that the English rats came out of their holes. Have the German successes at sea really broken the English spirit?” British prestige was badly shaken. But the spirit…

There was a rush to recruiting offices and, overnight, the British people lost their indifference to the faraway war – although not even the events of this morning could prepare them for the slaughter on the Western Front that was to come.

The Echo predicted: “The wanton, profitless, and deliberate slaughter of women and children has roused a spirit of determination to resist the designs of an apparently ruthless enemy.” The English spirit was not broken; it was in fact awoken.