In December 1914, the horror of the First World War was visited on three North-East coastal towns in a naval bombardment which lasted less than an hour but which awoke an enduring British fighting spirit. Chris Lloyd reports.

Shell shocked: after the bombardment, unexploded shells were discovered in the streets of Hartlepool

IT was a misty morning. Grey and dank. Suddenly, through the gloom, there loomed the black hulks of three warships. Shells burst from their guns with vivid orange explosions, and the streets of Hartlepool, Scarborough and Whitby ran red with blood.

The full horror of the First World War was visited upon an unsuspecting North-East. In a naval bombardment lasting little more than an hour, about 2,000 shells – some weighing a ton – rained down on the three coastal towns. More than 130 people were killed, several hundred were injured, thousands were made homeless.

The noise roared inland. They heard it as far away as Middleton in Teesdale. In Bishop Auckland, they thought it was a colliery explosion. But within hours, as the first refugees from the stricken districts started arriving with their personal possessions piled up in carts, the whole region realised it was at war.

Until eight o’clock on the misty morning of December 16, 1914, the war had been fought faraway on foreign fields. A few local boys had signed up with the whiff of an exotic adventure in their nostrils – fighting for king and country was a more glorious death than a grim, mundane demise down the local pit.

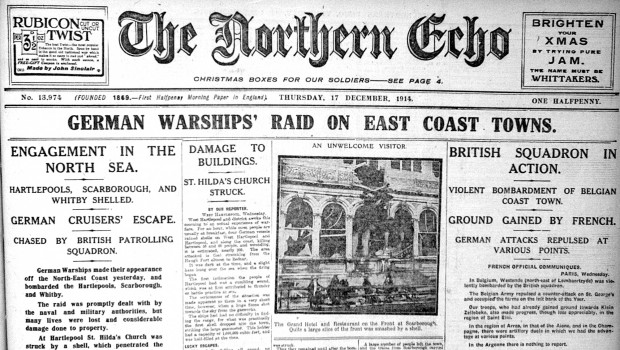

Anyone popping out for The Northern Echo that morning would have felt secure in the knowledge that the war would be over by Christmas. “Allies take the offensive and make good progress”, said the paper’s front page. “Substantial progress in Northern France.”

So Admiral von Ingenohl and Kaiser Wilhelm planned a rude awakening. They dared not throw their entire fleet into a full-blown naval battle, but they wanted to show the British that they were vulnerable in their own beds.

INlater years, it emerged that British Naval Intelligence knew what the Germans planned – but was prepared to sacrifice the people of the North-East coast to help win the wider war.

The day’s events began at about 7.50am when a couple of small British destroyers stumbled across a flotilla of German battlecruisers in the mist. After a brief exchange of fire, the out-gunned British hurriedly retreated, leaving the coast unguarded.

At 8am, the battlecruisers Moltke, Blucher and Seydlitz emerged out of the grey at Hartlepool and began their bombardment.

At the same hour, Derfflinger and Von der Tann opened up on Scarborough. As it had no defences, they targeted the Grand Hotel, pounding it with 35 shells.

On the Esplanade, John Duffield dashed to a phone to raise the alarm. As he pleaded with his wife to find shelter, a shell landed on top of her, killing her outright before his eyes.

“For days afterwards, her innocent blood stained the steps and pavement as a reminder of the horrific event, ” says Mark Marsay in his book, Bombardment!

The Day the East Coast Bled.

“Death and destruction was visited on Scarborough with all the ferocity of hell, the dogs of war let loose to run rampant through her desperate streets.”

At 14-months-old, John Ryall was the youngest of the town’s 18 victims. “His injuries extensive, ” says Marsay, “especially to his head which was laid open exposing his brain. He died in absolute agony some ten minutes later cradled in the arms of his distraught father.”

After 25 minutes of indiscriminate firing, Derfflinger and Von der Tann returned quietly into the mist.

Hartlepool’s hell was more enduring.

The battlecruisers kept up their bombardment for nearly an hour. The men of the 18th Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry in the Lighthouse Battery bore the initial brunt. The first shells killed Private Theophilis Jones. He was 29, a West Hartlepool teacher, the first soldier to die on British soil in “The Great War”.

He was quickly followed by Corporal Alix Oliffe Liddle, 25, of Linden Avenue, Darlington, and Private Walter Rogers, 25, of Bishop Auckland. Two stretcherbearers were also killed and a shell skidded off the battery’s concrete into the field behind, killing a donkey. There was nothing left of it but its tail.

How the story was reported in The Northern Echo, December 17, 1914

Despite the carnage, Battery Commander Dickie Trenchmann – monocle in eye, megaphone in hand – ensured the gun remained manned. Its first two shells fell shy. The third hit Blucher and killed nine sailors. The fourth jammed.

The gun should have been left for ten minutes to ensure there wasn’t a slowburning fuse, but Sergeant T Douthwaite bravely stepped in. He ordered his men back, removed the cartridge and, even though it might detonate at any moment, plunged it into a bucket of water.

The gun was again trained on the battlecruisers, and Douthwaite was later awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

In truth, though, the British popguns were just minor irritants to the heavilyarmoured Germans and they soon turned their big guns on the town.

MARGARET Hunter was killed by the railway line as she went to pick sea coal, “her body riddled with shell”. George Jobling in Dock Street said: “I was just going to get a drop of tea when all at once smash. . . I found three children among the bricks, two of them my son’s children. They had been killed. . .”

George Cornforth, 63, and his daughters Jane Ann, 17, and Polly, 23, were all killed when their house in Lily Road collapsed on them. Amy Watts, 22, died “dressing for business” when her attic bedroom was struck.

John Healy, 63, had just left Irvine’s shipyard when he was “struck in the back by a piece of shell which came out near his throat, killing him instantly”.

Democratically, The Northern Echo devoted a paragraph to the death of each of Hartlepool’s 123 victims, the last dying as Seydlitz fired the last shell at 8.52am and slipped back into the mist.

As peace returned to the stricken streets of Hartlepool, Whitby was wondering what had hit it. At 9am, Derfflinger and Von der Tann opened up, pounding it for 11 minutes, killing four people and hitting the ancient abbey.

Then they, too, slunk back into the mist.

On land, the recriminations began.

How could the Germans get so close without being challenged?

The Admiralty’s response was brusque.

“Open towns on the East coast must expect to be bombarded and we cannot help it. Those who are killed must be killed and their relatives who mourn must mourn. We are sorry, but this cannot be prevented. . . we cannot scatter our big ships about to prevent bombardments which, though deplorable, are devoid of military significance.”

No wonder that for weeks if not months afterwards, the people of Hartlepool camped out in barns away from the shore.

King George V, though, sent “a large number of pheasants” to the homeless, and each wounded person was given a pheasant feather.

In later years, we’ve learned that the battlecruisers didn’t appear out of the grey on December 16, 1914. British Naval Intelligence had intercepted a German signal on December 14 and knew what was coming. But if the East coast had been forewarned, the Germans would have known that their code had been cracked – and the British hoped to receive bigger pieces of information before being forced to reveal their hand.

So it had to look as if Britain was surprised by the raid. Scarborough and Whitby were given no warning of impending danger, while Fortress Command at Hartlepool received only this cryptic telegram at midnight on December 15: “A special sharp lookout to be kept along all East coast at dawn tomorrow. Keep fact of special warning as secret as possible.”

Indeed, it looked as if the raid had taken the British by complete surprise.

An ambush had been planned for the German ships at Dogger Bank on their homeward voyage, but the fog foiled it and the battlecruisers returned unhindered.

But the incident wasn’t quite as “devoid of military significance” as the British Admiralty had thought.

The Echo predicted: “The wanton, profitless, and deliberate slaughter of women and children has roused a spirit of determination to resist the designs of an apparent ruthless enemy.”

Indeed, in the weeks afterwards, indifference to the faraway war was replaced by a rush to recruiting offices. The British spirit had not been broken by the events; in all probability it had been awoken.