Looking back from the centrally-heated 21st Century at lives lived more than 100 years ago, they appear very tough and rather cruel. Memories 155 began to tell the story of Rifleman Edward Roberts, who lies beneath the only First World War headstone in Kirk Merrington churchyard. How did he – a Welshman serving in the Irish Rifles – end up in County Durham, we asked?

RESTING PLACE: The grave of Rifleman E Roberts in Kirk Merrington churchyard

FIRST of all, John Husband in Darlington has done some genealogical research. It starts in March 1859 with Jane Cheesemond marrying Charles Askew in the Auckland area.

Over the next 20 years, they had five children before, in September 1880, Charles died.

He was only 42, and his youngest child was just six.

Jane, with all those mouths to feed, didn’t hang around. In December 1880 – three months after becoming a widow – she remarried.

Her new husband was coalminer Christopher Henderson, who came from Sadberge. He had his two wonderfully-named children – Ezias, 12, and Ebzalah, ten – and within a year Jane had given him another two: very ordinarily named twins, Rose and Elizabeth.

So the 1881 census maker found Jane and Christopher living in Merrington village with their nine collective children aged between one week and 19 years.

Our attention is claimed by one of these children, Mary, who in 1899 married the Merrington blacksmith, George Richardson.

They had two children before George popped his clogs in June 1907. He was only 39.

So the 1911 census maker found Mary, 38, living in 5, Chapel Street, Kirk Merrington, which was crammed with various relatives that cruel twists of fate had rendered in need of a roof.

LOOKING BACK: Kirk Merrington in about 1920. Chapel Street is the rough road that rises up to the right of the main road, with Edward and Mary’s home at the highest point. The children in the foreground are playing in what remains of a pond which was once in the centre of the road – now Ramshaw and Coronation terraces occupy this spot. Picture courtesy of Ann and Dennis Arthur

As well as her two girls, her widowed mother, Jane, 70, was living with her along with her step-sister Elizabeth Henderson, 40, and her nephew, Samuel Henderson, eight.

How they all squeezed into the terraced house, we shall never know, but there was still room enough for a boarder: Edward Roberts, 26. He was born in Wrexham, and worked as a gas regulator at some coke ovens, probably in Spennymoor.

Despite the 12-year age difference, Mary married Edward in December 1911. She was already three months pregnant, and gave birth to Edward’s daughter, Frances, in June 1912.

Then the First World War broke out.

Geoff Carr, of Aycliffe, has been looking into the this part of the Merrington mystery.

He discovered that Edward enlisted in the 1st Battalion of the Royal Irish Rifles in Manchester and was sent to the Somme.

The Rifles were ravaged by battles during 1915 and Edward ended up in Kirk Merrington churchyard, far from the front line, where his headstone says he died on November 18, 1915.

To provide the final details, his death certificate was needed. Geoff applied to the English and Welsh authorities but despite there being several Edward Roberts who appeared to fit the bill, none of them turned out to be Merrington’s Edward Roberts.

MISSING HOUSE: Chapel Street where Edward and Mary Roberts lived. However, number 5 is no longer standing

Then Geoff had the inspired idea of applying on the off-chance to Scotland.

And there was our man, dying in Stobhill Hospital in Glasgow – a large Army hospital with its own railway station so that ambulance trains carrying the wounded could pull almost into the wards.

Geoff said: “Genealogical research is totally addictive, as you really get a thrill from using the clues and finding the evidence. You also feel like you know the people and how their lives were going.”

Edward’s death certificate told how his life came to an end.

Cause of death was: “Gunshot wound of pelvis, 61/2 months, rupture of urethra 61/2 months. Inflammation of bladder and kidneys 2 months.”

Six months before his death, Edward’s battalion was suffering large losses at the Battle of Neuve Chapelle.

Whether he was sent straight from the Somme to Glasgow for treatment, or whether he came home to Mary and her crowded house for recuperation, we don’t know.

But in September 1915, a secondary infection set in, and two months later, Edward died.

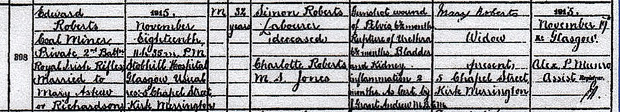

OFFICIAL RECORD: Rifleman Roberts’ death certificate, discovered by Geoff Carr, in Scotland

The death certificate has one final little nugget to impart. It says Mary was “present” at her husband’s death in Glasgow.

Aged 37, she was a widow for a second time. She ran a shop in the village which had to support her two teenage daughters plus three-year-old Frances who had just lost her father. Plus other bits and bobs from her extended family – life for her must have felt very cruel and very tough.

ANOTHER note: local Merrington historians Ann and Dennis Arthur bumped into The Northern Echo’s photographer David Wood as he was taking today’s pictures of Rifleman Roberts’ headstone.

Ann looked out her minutes of Merrington Parish Council and found that in December 1919, there was a debate about how the £130 left in the Soldiers and Sailors Fund could be used to help returning soldiers and the village’s six war widows.

The minutes name the widows as Mrs Oyston, Mrs Maughan, Mrs Cant, Mrs Lowery, Mrs Tunstall and, of course, Mrs Roberts. The £130 won’t have gone far. . .

Does anyone know the stories of the other five military men of Merrington?

OF the 1,045 Darlington men known to be killed in the First World War, only one died on Christmas Day.

CASUALTY: Captain George Coates

That was Captain George Coates who, by coincidence was the joint managing director of the Whessoe Foundry with his brother, Alfred.

Whessoe, who, you will remember, featured in Memories last week.

The brothers took over the foundry in 1913 following the death of their father, Thomas.

His picture appeared last week as he was the engineer who turned the foundry into the largest storage tank manufacturer in the world.

Capt Coates, of Elton Gardens, Darlington was 41 when he died on Christmas Day 1915, leaving his wife, Ethel, and their five children. Sadly, for all of his undoubted bravery, the captain’s death was a mundane one.

He appears to have joined the 5th Durham Light Infantry early in the war, only to resign due to ill health. He could probably have seen the war out in the foundry which was assisting the war effort but instead, in the spring of 1915, he rejoined the 2-9th DLI. He trained with them in Sunderland and then Hertfordshire in preparation for overseas service. However, before he could leave, he fell seriously ill and was brought home.

“That was about two months ago, ” said the Evening Despatch on December 27, 1915. “After a few weeks’ illness he improved, but subsequently had a relapse. On Christmas Day he was in good spirits, and had just finished his dinner when he collapsed and died.”

He is buried in West Cemetery.

OFthe 1,045 Darlington men known to be killed in the First World War, only one died on Christmas Eve.

That was Private Charles Preston, 27, who succumbed the day before Capt Coates.

The two soldiers were at either end of the social scale.

Capt Coates was an ironmaster; Pte Preston was an iron foundry labourer.

He lived in John Street, a humble terrace, and joined the 22nd DLI. Like Capt Coates, he never saw action in a foreign field. He was either injured in an accident or caught an illness, and he died in the workhouse infirmary off Yarm Road.

He was buried in West Cemetery the day after Capt Coates, but his mundane death does not appear to have warranted a mention in the local papers.

SURVIVOR: William Thomas Dobson of the DLI, right

NOT all of the First World War stories end in the death of the soldier concerned.

Paul Dobson of Bishop Auckland has sent in these details of his grandfather, William Thomas Dobson, who was born in Easington Lane in 1889, and worked in Elemore Vale colliery.

When the war broke out, he joined the Durham Light Infantry and, likemanyminers, his underground skills were used tunnelling beneath German trenches and blowing them up.

Somewhere on the Somme, William was wounded. “He said that they wanted to amputate his leg but decided against it, ” says Paul.

Instead, William ended up in Sunderland Children’s Hospital with other injured servicemen, and he managed to keep hold of both of his legs.

“Ironically, ” says Paul, “he lost his right hand in an accident in the pit in 1928, but he would walk miles with his dog until just before he died in 1975, age 86.”