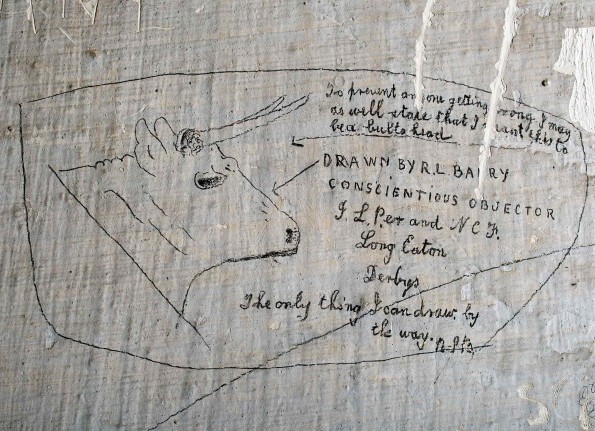

In this inscription Richard Lewis Barry, a socialist conscientious objector from Long Eaton, Derbyshire, described the futility of fighting

GRAFFITI which reveals an often-forgotten chapter of the First World War is to be saved from crumbling away to dust.

Hundreds of pencil drawings, political slogans, portraits, hymns and poetry were scrawled on the walls of the 19th-century cell block at Richmond Castle by conscientious objectors who were incarcerated there.

But they are falling victim to time – rainwater has seeped through cracks in the roof and walls and high levels of moisture and damp mean the layers of lime wash and plaster are flaking off, taking the graffiti with them.

The cells at Richmond Castle in North Yorkshire.

However now they will be protected by English Heritage as part of a £365,400 project which will see the roof and walls repaired, the levels of moisture brought under control and treatment for the graffiti most at risk of being lost.

The graffiti was the work of the “Richmond Sixteen” – conscientious objectors including Quakers, Methodists, Jehovah’s Witnesses and socialists who were imprisoned at the castle before being shipped to France to face court martial.

“These graffiti are an important record of the voices of dissent during the First World War,” said English Heritage chief executive Kate Mavor.

“It is remarkable that these delicate drawings and writings have survived for 100 years. Now we can ensure that they survive for the next century and that the stories they tell are not lost.”

Once the surfaces of the walls are stabilised and moisture is reduced so people breathing or moving around in the rooms will not damage the graffiti, the public will be able to view the cells for the first time in 30 years.

Bull’s Head by Richard Lewis Barry-About 1916. A bull’s head was the only thing which Richard Lewis Barry believed he could draw.

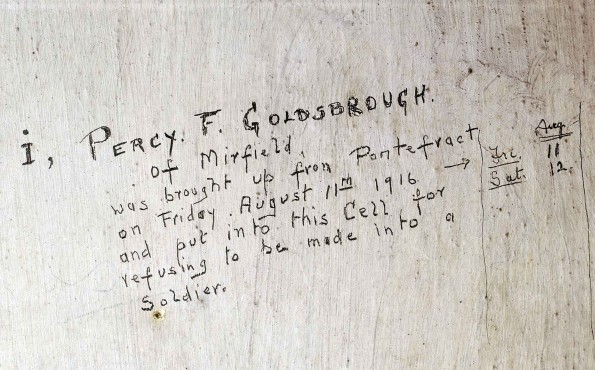

Percy Fawcett Goldsbrough was put into the cells for disobeying orders. Soon after making his mark on the cell wall he was court martialled, sentenced to 112 days’ imprisonment and transferred to Durham civil prison.

Bert Brocklesby’s fiancée, Annie Wainwright – evidently at the fore of his thoughts while he was imprisoned at Richmond,.

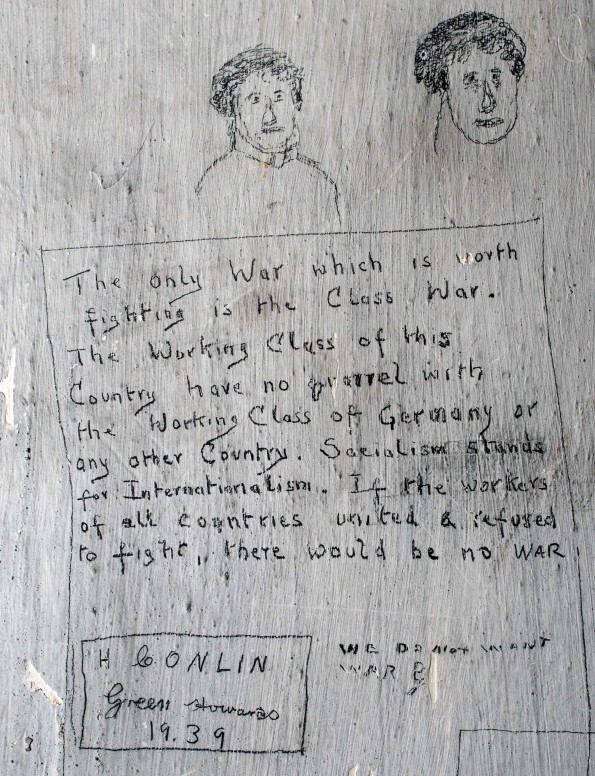

Class War – by G. In his inscription, this socialist conscientious objector asserts his belief that ‘The only War which is worth fighting is the Class War.’

Until then, they will be able view them virtually, on the English Heritage website, seeing writings such as the words of socialist Richard Lewis Barry from Derbyshire: “You might as well try to dry a floor by throwing water on it, as try to end this war by fighting.”

The men were incarcerated in May 1916 for refusing to fight after conscription was brought in for the first time.

They were taken from their cells on May 29, and sent to France where a court martial passed a sentence of death, which was immediately commuted to ten years of hard labour on the orders of Prime Minister Herbert Asquith.

Among them was Norman Gaudie, a talented sportsman who played for Sunderland and Darlington football clubs. His daughter-in-law, Marjorie Gaudie, 78, lives in Osmotherley, near Northallerton.

“He acted from the deepest conviction that all life is sacred. He knew it was wrong to take a life and so he refused to fight. He was prepared to die for his belief,” she said.

“He and the others paved the way for conscientious objection to be able to come into force, for it to be legal.”