CURATOR: Amy Barker

PENNED in miniscule handwriting in small leatherbound notebook the text is so tiny it is hard to read without leaning up close.

But what it lacked in size was more than made up in the enormity of the impact of its message.

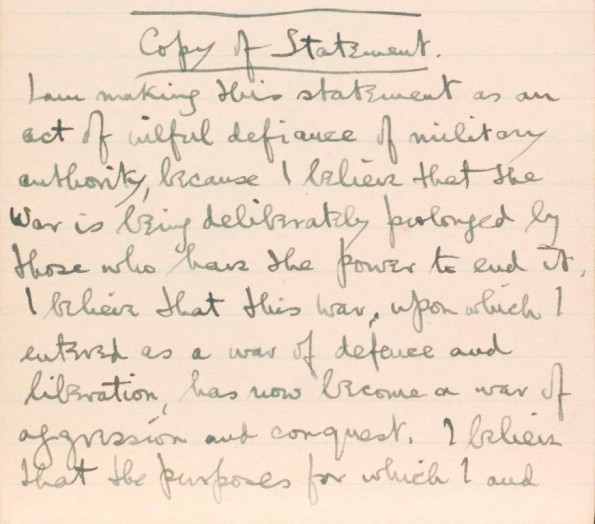

Siegfried Sassoon’s declaration against war was considered and to the point: “I am making this statement as an act of wilful defiance of military authority because I believe that the war is being deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it.

“I am a soldier, convinced that I am acting on behalf of soldiers.

“I believe that the war upon which I entered as a war of defence and liberation has now become a war of aggression and conquest.”

Read out in the House of Commons in 1917 and printed in The Times, the officer’s sentiments the shook establishment to the core.

Sassoon’s fair copy of the final version of his Finished with the War: A Soldiers’ Declaration is one of the highlights of an exhibition at the Hatton Gallery, in Newcastle, examining the horror endured by soldiers during the First World War.

POIGNANT: A Soldier’s Declaration by Siegfried Sassoon

Screaming Steel: Art, War and Trauma 1914 to 1918 explores the creative responses to the industrialised killing fields of Europe, which resulted in some of the most important 20th century British art and literature by artists and writers such as Sassoon, Paul Nash, William Orpen.

Curator Amy Barker, who secured exhibits from national collections, including the British Museum, National Portrait Gallery and Tate says: “It was a really big deal for such a high profile person as Siegfried Sassoon to have taken the stand he did.

“What he said wasn’t acceptable to the establishment. They couldn’t do anything like court martial and shoot him so they had him declared as suffering from shell shock and treated him at Craiglockart War Hospital (near Edinburgh).

“Whether or not he had shell shock I’m not entirely sure. He’d already won the Military Cross and went back to the trenches and survived. Despite speaking out against the war, he couldn’t have been braver.”

In a cabinet close to Sassoon’s journal and poems is another fascinating document encapsulating Sassoon’s first meeting with fellow poet Wilfred Owen – and fictionalised in Pat Barker’s Regeneration Trilogy.

It is the first draft of Owen’s Anthem to Doomed Youth.

Ms Barker said: “You can see the pencil annotations with Sassoon’s suggestions.

“Anthem for Dead Youth, became Anthem for Doomed Youth. And the first line “what passing bells for those who die so fast” became for those who die as cattle.

“It beautiful to see it, because you can see the process of change and development and improvement – making it scan better to give the poem more impact.”

An important part of the exhibition is around perceptions of mental health and shell shock, says Ms Barker.

“At the beginning of the war mental illness was seen as a degenerate thing, suffered by people with bad heritage or with bad nutrition . . . by poor people.

“The great sons of the British families who went to Oxford and Cambridge and Eton never suffered things like this.

“Obviously there was hysteria, which woman suffered from. But the First World War just threw all that up in the air.

“It brought change in fundamental understanding of mental health issues, because how could all these young men from be suffering from hysteria?

“There was the realisation they were not just hysterical.”

By the end of the war 80,000 soldiers were suffering from shell shock, when at the beginning of at beginning of war 80,000 was the size of the whole British Army that was sent out to France.

Ms Barker says: “Today we know it as post traumatic stress disorder, which is recognised and treated as such.

“It is only one tiny aspect of of the spectrum of mental illness.

“What I hope the exhibition does is make people think of mental illness in a different way, because it is something that could be experienced by any one of us.”

The exhibition also includes a series of lithographs by Paul Nash, prints by CRW Nevinson, paintings by George Grosz, Haydn Reynolds Mackey and William Orpen, as well as prints from the Otto Dix series Der Kreig.

A particularly poignant item is a small number of olive leaves from the tree under which Rupert Brooke was buried on the Greek island of Skyros. Beside it is the last sad letter he wrote to his beloved, the actress Cathleen Nesbitt.

Dated March 18 1915, from “Off Gallipoli”, it reads: “Oh my dear, Life is a very good thing. Thank God I met you. Be happy & be good. You have been good to me. Goodbye, dearest child – Rupert.”

The exhibition runs until December 13. Admission is free.