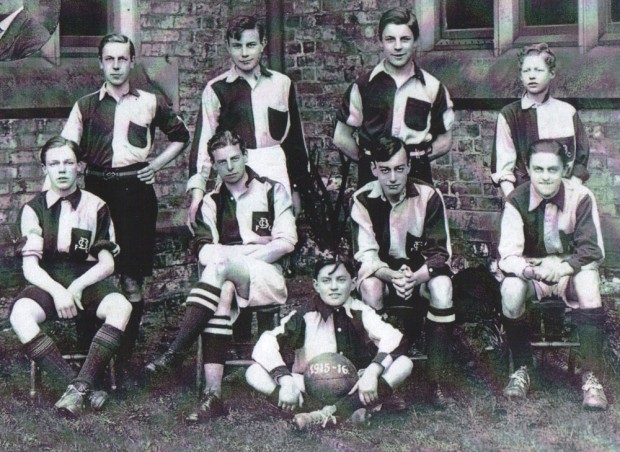

PLAYING ON THE WING: Darlington Grammar School football team, 1915/16. John Worstenholm is standing on the left; Harold Easby is seated second from the right

Two Darlington 19-year-olds took to the air to fight for the country in the Great War. Memories recalls their parallel lives and valiant deaths.

John Worstenholm and Harold Easby were born nearly a year apart in Darlington at the end of the 19th Century. In their short school lives together, they shared much, including a love of sport. And – only three months apart – they shared the same deaths, their biplanes shot out of French skies during the First World War. They also shared the same age – 19.

WORSTENHOLM was the eldest, born in 1897, the only child of the editor of The Northern Echo, and, by all accounts a brilliant student who was plucked from Cambridge University to become a pilot.

Easby was 11 months his junior, the son of a painter and decorator who had a wallpaper shop in Northgate. He joined Worstenholm at the Queen Elizabeth Grammar School, in Vane Terrace in 1910, and together they played for the school football team in 1915.

Easby was the better sportsman of the two. He captained the school cricket team and in the house cross-country run, finished ahead of Worstenholm. They also jousted with one another in the debating society. In early 1915, Easby proposed a motion in favour of votes for women. Worstenholm led the opposition. The debate was interrupted by “a militant suffragette” who was allowed to speak – she was said to have caused some amusement – but not allowed to vote. Worstenholm won the day.

He was the academically superior of the two. In examinations in 1914, taken just as the First World War was beginning, he came eighth out of 2,839 in the country for French, and was nearly as highly ranked in Latin and Scripture.

He won two scholarships, and left the school in the summer of 1916, bound for Cambridge University. His matriculation, though, was delayed by the death of his mother, and after just a couple of months of studying he volunteered to join the Artists’ Rifles.

The Artists recruited painters, musicians, actors and architects, and was particularly popular among public school and university students.

We can only guess what Worstenholm’s father, Luther, made of his joining up. Luther was a Quaker and probably a pacifist. In 1908, he became editor of the Echo, a paper which had endured public hostility in the jingoistic days of 1899 when it had opposed the Boer War.

Luther maintained the editorial line. On the morning of August 4, 1914 – the day Britain declared war on Germany – he wrote: “Civilisation is at stake, and we would have preferred to see Britain strong in her attitude of neutrality so that she could step in sooner or later to stay the terrible drain upon life, treasure and trade.”

His plea for Britain to stay out having been rejected, the following day he wrote:

“Throughout Europe there are millions of aching hearts left behind the marching troops. . .War has been declared, and we are bound to meet it in the spirit of sane Englishmen.”

Luther, still grieving his wife, became another of those aching hearts at Christmas 1916.

By Easter 1917, his 19-year-old son had transferred from the Artists into the Royal Flying Corps, stationed at Oxford, where he was training to be a pilot.

AT the same time, Harold Easby, his former playmate, left Darlington Grammar School and joined the Royal Naval Air Service as an Observer Sub-Lieutenant.

Britain at this time was desperate for airmen. It had been slow in seeing the need for an air force and had entered the war with just 180 operational aircraft. These were used initially for reconnaissance flights over enemy lines.

At first, opposing fliers exchanged smiles and waves as they flew past each other.

Then they started lobbing bricks and ropes (hoping to snag the other chap’s propellor) at each other, and then hand grenades.

On October 5, 1914, a French pilot, Louis Quenault, took to the air with a machine gun and shot down a German plane – the first “kill”. The war had suddenly moved off the land and the sea and up into the sky.

When the Battle of the Somme began in July 1916, the better-equipped Germans had aerial superiority over the trenches, with the British desperately trying to recruit pilots to catch up. April 1917, though, was “Bloody April” as the new British pilots were poorly trained and easy targets for their more experienced counterparts.

In the immediate aftermath of Bloody April, the two old Darlingtonians found themselves in the air services.Were they worried that they too would be swept away on the bloody tide, or did they share the immortality of youth – that confident certainty of being too young to die?

And all too soon, they found themselves in the firing line.

Second Lieutenant John Worstenholm was the first to succumb. Havingmastered all he needed to know about flying a plane in three months, he was sent to the Somme, where he lasted five weeks.

Early on September 25, 1917, he was on a reconnaissance mission with the Battle of Menin Road Ridge taking place beneath him. He was in an RE8 – a Reconnaissance Experimental 8 – two-man biplane with observer, Frank McCreary, who faced backwards. On McCreary’s previous mission, he had been injured and his pilot killed.

At 8.45am, they came under attack from an enemy Albatros fighter.

“Hold on tight, I’m taking her up, ” where his last words as he aimed the plane at a protective bank of cloud. Then he was hit at least twice in the stomach with such force he was lifted out of his seat.

He slumped dead onto his joystick, sending the plane spinning towards the ground.

FOR McCreary, hit in the left hand, there was no escape. He had no parachute. So he stood up in his cockpit, turned around and using his one working arm, with the ground hurtling towards him, somehow shoved the weight of Worstenholm’s body off the controls.

McCreary, who had had no training in how to fly a plane, yanked the plane out of its spin, forced it to fly upwards so fast that he feared he would pass out, and thenmanaged to get it level – only to find he had now created the perfect target for the Albatros to renew its attack.

He jumped down into his own seat and, single-handedly, fired his Lewis gun at the enemy, seeing it off.

Regaining his feet, he tried to gain control of Worstenholm’s joystick. Through the blood splattered on the dials, he could see he was at 1,000ft.

He could see the tents of an army encampment beneath him. Then he could see the colour of the Australian soldiers’ uniforms as they ran for cover. Then he slipped. . .

“He managed to grab hold of the gun ring with his good hand just as he was about to slide over the side of the fuselage, ” says Steve ‘Buster’ Johnson in his book, For God, England and Ethel. “Pulling himself back into his cockpit, he watched helplessly as images of sky and earth spun round in front of him, reminding him of the merry-go-round rides he had taken as a child.”

Amazingly, the RE8 missed the soldiers and their tents and belly-flopped into trees, catching fire but throwing McCreary clear. Apart from a few scratches and the bullet wound to his hand, he was unharmed, and was awarded the Military Cross.

Worstenholm’s body was retrieved from the wreckage, once the flames had died down, and was buried at Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery, near Ypres.

Three months later, Harold Easby, his former teammate on the Trinity Road pitches, followed him to a French grave.

On January 7, 1918 – only eight months after leaving school and only a week after his 19th birthday – was flying in an Airco DH4 tractor biplane day-bomber when it crashed at Fort Mardyck, near Dunkirk.

It is believed to have been on a training run.

Both he and the pilot, Flight Sub-Lieutenant Cyril Barber, a 23-year-old Canadian from Port Credit, Ontario, were killed and were buried in Dunkirk Town Cemetery.

Easby’s parents, Thomas and Mary of 2, Flora Avenue, Darlington, donated a guinea towards the cost of the school memorial board, on which the two ex-pupils’ names appear along with 84 others from the Great War.

Luther Worstenholm is not on the list of donors – perhaps he saw the board as a commemoration of war. In 1919, he urged Echo readers: “A s a nation, we have to outgrow the passions of war and realise that the victories of peace are alone permanent and satisfying.”

He did, though, support Remembrance Day, when it was introduced in 1919 (see over) because he believed that it would promote the cause of peace.

He wrote: “It serves to remind those who would keep alive the fires of hatred that they will find no encouragement from the sorrowing mothers and fathers of the slain.”