The battalions of the Durham Light Infantry paid heavily for its infamous assault on the Butte de Warlencourt, an ugly mound of land dubbed ‘that miniature Gibraltar’. Chris Lloyd counts the cost.

TO THE TOP: A sketch by Capt Robert Mauchley entitled “Attacking the Butte de Warlencourt”

THE tree-lined D929 runs dead straight through the flat fields on the northern bank of the River Somme. Just one hillock stands out: the Butte de Warlencourt, a prehistoric burial mound.

Its past gives it a presence. Even though today it is only about 50ft high, it grabs the eye of the travellers on the road as it looms large over the landscape, in much the way that Roseberry Topping stares down on the Tees Valley.

Exactly 100 years ago this week, three battalions of Durhams were fighting in the fields for the Butte – fighting as much against the thick, porridgey mud as they were against the Germans who were dug in deep inside the mound.

They were fighting even though the Butte wouldn’t have been much military use even if they had captured it – it was so exposed that it attracted enemy fire, and it was such an obvious target that it would have been difficult for the British to hold.

BORN LEADER: Roland Bradford

Lt Col Roland Bradford, of Witton Park and Darlington, was leading the 9th Durham Light Infantry against the Butte. From its chalky peak, an observer would have been able to see the fields at Eaucourt l’Abbay where, a month earlier, he had won the Victoria Cross for his bravery in battle.

But even he thought the Butte – which is French for “mound” – was “of doubtful value” and “of little use”.

He later wrote: “The Butte de Warlencourt had become an obsession. Everybody wanted it. It loomed large in the minds of the soldiers in the forward area and they attributed many of their misfortunes to it. Newspaper correspondents talked about ‘that miniature Gibraltar’. It seems that the attack was one of those tempting and, unfortunately, frequent local operations which are so costly and which are rarely worthwhile.”

And it was the Durhams that would pay the cost. As well as Bradford’s 9DLI, on the left, the 8DLI were on the right and the 6DLI – recruited mainly from the Bishop Auckland area and rejoicing in the nickname of the “black buttoned bastards” – down the centre, like a football formation.

But it was so wet that their match was postponed for a fortnight as, day after day, it came down like stair-rods. The opening of November was a little drier, but a heavy shower before kick-off filled the trenches and ensured the field of play was as bad as any infantry ever faced.

“The muddy ground, torn by shellfire and churned into deep ~porridge by heavy rain, was from knee to thigh deep,” writes Aycliffe historian Harry Moses in his book, The Fighting Bradfords.

Zero hour was 9.10am on November 5. “The officers’ whistles sounded the advance,” wrote Lance Corporal Harry Cruddas, of 6DLI. “Immediately the first wave mounted the trench, they were met by a terrific and annihilating fire and crumpled up like snow in summer.”

Even though they had to advance just 300 yards to the Butte, 6DLI could not make any headway. 8DLI fared a little better, but when they got within 30 yards of the mound, under heavy fire from the Germans in front, they were suddenly struck by British artillery from behind and Australian artillery from the side.

Those who were not killed outright, fell from their wounds, and drowned in the mud.

Perhaps because the other battalions took all the fire, 9DLI, led by Lt Col Bradford, made it out of their Maxwell Trench, across No Man’s Land and up to the top of the Butte within an hour so they could look down on the D929.

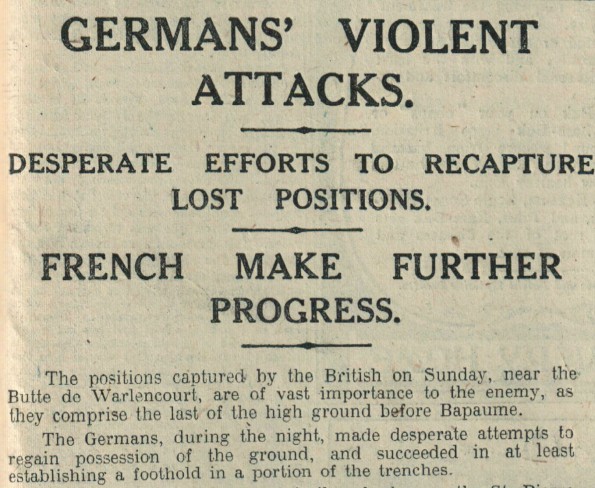

The Northern Echo, of November 7, 1916, giving the briefest of details about the loss of the Butte de Warlencourt

But the Butte was a honeycomb of trenches – the enemy was ensconced as tightly as a nest of ants beneath heavy stone workings that had first been dug out during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870.

Lt Col Bradford, whose home was in Darlington’s Milbank Road, wrote: “Over 100 German soldiers were lurking down in the dark warren of dugouts and tunnels beneath and around the Butte. So began a murderous game played out with bomb and bayonet, with little or no quarter on either side.”

Plus, reinforcements were able to reach the Germans.

They counter-attacked at noon. 9DLI held on.

They counter-attacked at 3pm, knocking 9DLI back – but still they held the Butte.

“About 6pm, the Germans made a determined counter-attack preceded by a terrific bombardment,” wrote Lt Col Bradford. “A tough struggle ensued. But our men showed the traditional superiority of the British in hand-to-hand fighting, succeeding in driving out the enemy.

“The 9th DLI was now getting weak, but it was hoped that the Bosche had now made his last counter-attack for that day.”

He hadn’t. Further reinforced, he came again at 7.15pm, all but forcing the “Gateshead Gurkhas” to relinquish their grip on the Butte.

“At about 11pm, battalions of the Prussians delivered a fresh counter-attack,” wrote Lt Col Bradford, an old boy of Darlington’s Queen Elizabeth Grammar School. “They came in great force from our front and also worked round from both flanks. Our men were overwhelmed. Many died fighting, others were compelled to surrender. It was only a handful of men who found their way back to Maxwell Trench and they were completely exhausted by their great efforts and the strain of the fighting.”

Back where they had begun, the Durhams began counting the cost. The 6th and the 8th battalions had lost, in one way or another, about 1,000 men between them. 9DLI’s figures are more precise and of a similar magnitude: 42 killed, 230 wounded, 157 missing.

It later transpired that in total, 273 Durham men had died.

And all for the Butte that was “worth bugger all”.

Despite the fierceness of what they had come through, the survivors stayed in the frontline trenches around the Butte until they were withdrawn for rest and recuperation on November 16. By then, the Battle of the Somme had become bogged down in the Butte’s mud, and the mound remained in German hands until they retreated from it on February 24, 1917.

Finally having topped the French topping, the British erected on its chalky peak three rudimentary wooden crosses – one for each of the three Durham battalions.

The Butte crosses in Durham Cathedral were reunited earlier this year after 90 years apart

In 1926, the crosses were taken down and brought home, in lieu of the men who had lost their lives. One went to St Andrew’s Church, in Bishop Auckland; another went to the Church of St Mary and St Cuthbert, in Chester le Street, and the third was positioned in Durham Cathedral.

In July 2016, to mark the Battle of the Somme, the three Butte crosses were brought together in the cathedral’s DLI Chapel where they stand arm to arm just as they had once stood on top of the hillock overlooking the D929 were so many Durhams, fighting hand-to-hand, had died exactly 100 years ago.