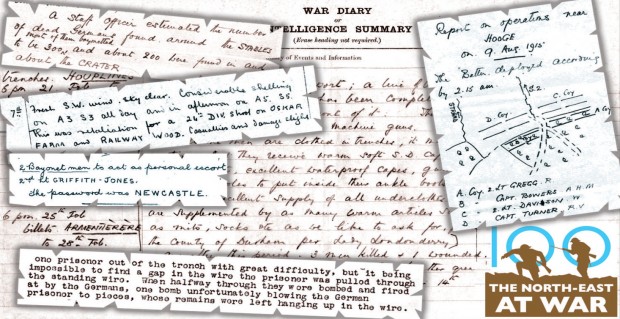

FIRST-HAND ACCOUNT: Pages from diaries of the First World War kept by soldiers of the 2nd Battalion Durham Light Infantry

More than 1.5 million pages written by British soldiers describing life on the front line during The First World War are being published online by the National Archives. Gavin Engelbrecht dips into one remarkable account.

WRITTEN in neat copperplate with a sharpened pencil, the opening diary entry is almost an understatement. “Order to mobilise received,” it notes. “On the night of August 4, 1914, immediately after the declaration of war Major Mander, assisted by Capt Hare and Lieut Yate with 30 men, seized a German merchant ship on the Tyne.”

So began the First World War for 2nd Battalion the Durham Light Infantry, as a detachment based in South Shields boarded a German steamer and marched its crew to a police station – possibly becoming the first regiment in action.

The diary author, like many, may have thought he would get over to France and home again before Christmas. But the ensuing document was to run to 680 pages, detailing everything from the momentous to the mundane, as 1,400 men made the ultimate sacrifice.

Released this week, as part of 300,000 pages of First World War diaries which have been digitised, the diary offers a fascinating insight into the day-to-day experiences of soldiers on the Western Front. Citizen historians have been encouraged to read them in a bid to unearth new discoveries about life at war.

In an unprecedented opportunity for academics and the public, the National Archives is making the first batch of diaries from France and Flanders available online – and once complete it will comprise more than 1.5 million pages – opening them to a global audience for the first time.

The Northern Echo downloaded 2nd DLI’s diary for a mere £3.36, allowing one to page through these first drafts of history at a mouse click. It is the immediacy of the entries that is captivating – and, with the benefit of hindsight, what goes unsaid is almost as interesting.

The 2nd DLI proceeded to France on September 10, 1914, landing at St Nazaire and at once moving to reinforce the hard-pressed British Expeditionary Force on the Aisne. The daily roll call of dead and wounded is perfunctory – the officers individually named, while the remainder fall under the category OR (other ranks).

The regiment moved to Flanders, to places with names which still resonate, such as Ypres, the Menin Road, Zonnebeck and more.

The only hint of the appalling conditions are occasional references to “considerable rain making the trenches unpleasant”. There is no mention of the rats or lice or ubiquitous stench of death.

One entry, on February 15, 1915, has “nothing particular for report”. It goes on “to show how men are clothed in the trenches, it may be mentioned that they received warm soft caps, fur waistcoats, excellent waterproof capes, gum boots, cork soles to put inside ankle boots, besides an excellent supply of all underclothes.”

In the next sentence it records “three men killed and one wounded”.

MUCH of the time is recorded in billets, cleaning up drying clothes, route marching and digging trenches or preparing breastworks. A programme of work stipulates physical training, squad drill, arms bayonet instruction and (not to forget) saluting.

To keep the men on their toes they were periodically ordered on raids, or enterprises, as they were referred to. The aim was to secure at least one German prisoner, who would then be interrogated for information.

Enterprise report No 11 observes: “The prisoner was pulled through the standing wire. When halfway through they were bombed and fired at by the Germans, one bomb unfortunately blowing the German to pieces, whose remains were left hanging up in the wire”.

The men were nonetheless praised for their gallantry by their superiors, who rued their “pure bad luck” at losing their prize.

The list of those evacuated through ill health make interesting reading too, and include ailments as such as sprained ankles, piles, conjunctivitis, tonsillitis – and a few early references to shell shock.

AMONG the key engagements documented is the battle of Hooge, in the Ypres salient. Using flamethrowers for the first time, the Germans had broken through the British lines and captured a newly-blown crater.

But, on August 9, 1915, the DLI helped retake it.

A blow-by-blow account, with reports added hourly, speak of obliterated trenches, difficulties sending up supplies, 125 men passing through the battalion first aid post by lunchtime and eventual losses of 498 men.

While most entries are clinical “a staff officer estimated the number of dead Germans found around the stables to be 300 – most of them bayoneted – and about 200 were found in and around the crater”.

By the end of the first year of the war, 53 officers and 1,555 OR had been killed or wounded.

By 1916, the regiment was on the Somme, and in 1917 at Hill 70 and Cambrai. In 1918, they were again on the Somme, then moved to Flanders in the spring, taking part in the fighting retreat as the German’s advanced through Baillieul to Kemmel.

2nd DLI were in action during the Allied advance in Flanders later that year and returned to the Cambrai area during battles of the Hindenburg Line. They were billeted around Bohain at the Armistice on November 11, 1918, and were selected to march into Germany as part of the occupation force – being the only regular battalion of the regiment to remain in theatre throughout the full period of the war.

William Spencer, author and military records specialist at The National Archives, said making the diaries available online allowed people across the world to discover daily activities, stories and battles of each unit for themselves.

“It’s interesting because it’s humanising it. War is a de-humanising thing,” he says.

To visit the online records, go to national archives.gov.uk