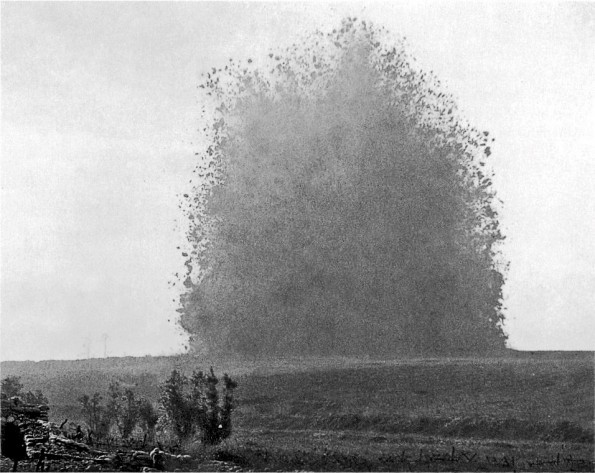

FEARSOME: The explosion of the mine at Hawthorn Ridge on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. The Durham Pals were stationed at Auchonvillers while the tunnels were being dug beneath Hawthorn Ridge

CONDITIONS in the Durham Pals’ sodden camp in the woods were so bad 100 years ago that most were relieved to go back into the trenches.

On the afternoon of Maundy Thursday – April 20, 1916 – the 18th Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry – commonly known as the “Durham Pals” because groups of friends had been encouraged to join it – received orders to return to their old positions near Auchonvillers in northern France after more than a fortnight in the reserve.

They’d spent 16 days doing exhausting work in relentless rain, living in windowless wooden huts while repairing trenches and keeping the supply lines moving. Little wonder that several of the Pals expressed relief to be back facing snipers and mortar fire.

The official war history of the battalion recorded that “everyone was glad to leave the dripping wood and take over our old trenches”.

Private William Weatherley, a Durham teacher, wrote home: “One could almost detect signs of relief when the next move to the trenches was announced.

“We were going into the firing line, but that implied something approaching a real rest compared with what we had had.”

The Pals’ second visit to the frontline trenches would last for only four days, which they seem to have survived without serious casualties despite what seems to have been a step up in hostilities and dreadful weather.

Pte Weatherley wrote: “The elements during the first few days were very unfavourable and we gained some idea of what trench life at its worst was like. Water and mud were almost knee deep and added to the danger of being shot was that of being drowned, especially those of us engaged in carrying rations.

“The humourous side of life was not entirely lacking. To see two men lugging a heavy container and endeavouring to pass safely by stepping on floating boards was to witness a smart piece of juggling.

“To prepare dug-outs in the side of the trench in order to provide some protection from the elements and to return at 2am to find the same dug-outs fallen in, all ones belongings buried, and the rain still falling was almost beyond the limits of tolerance and speech.

“Easter Sunday (April 23), however, introduced us to another spell of fine weather and matters gradually improved.”

Between the two opposing armies lay No Man’s Land, largely flat and featureless, only 200 yards at its narrowest point up to 500 yards at the widest. Across this expanse, German and British snipers took aim, and trench teams lobbed mortars at each other.

Preparations were now well underway for the coming Big Push and the trenches were busy. Both sides regularly ventured out into No Man’s Land under cover of the night, to plant or cut barbed wire, gather intelligence, raid the opposition trenches and capture prisoners.

On the British side, miners were digging three tunnels out into No Man’s Land which would allow mortar teams to pop up just 30 yards from the German front line in the hours before the attack.

Almost 60ft below the surface, a fourth great tunnel was being dug which would stretch out to below the German positions on Hawthorn Ridge and would be packed with 40,000lbs of explosives to be detonated just before the British attack.

Mining in peacetime was notoriously dangerous; mining on the battlefield was even more so. The battalion war history recorded: “This tour our patrols began to operate actively for superiority in No Man’s Land and did creditable work, while the enemy on his side was more active with trench mortars.

“The weather was much better and good progress was made in improving the line.

“After an explosion in one of our mines in the Redan, excellent rescue work in spite of smoke damp was done by Private WJ Warwick of B Company.”