Nurses in front of an ambulance train, 1916. Picture courtesy of the National Railway Museum, York

Ambulance trains bringing back the wounded from the front were so comfortable, one nurse reported, that the casualties could not sleep. The railways carried the soldiers off to the First World War frontline, and then they brought many of them home again – on ambulance trains.

From February 1915 to February 1919, 1,260,506 casualties were handled by railwaymen at Dover: they unloaded 4,076 boats full of injured men and loaded them onto 7,781 ambulance trains.

The ambulance trains carried them homeward, for treatment and, hopefully, recuperation.

The special trains stopped at “receiving stations” – on the East Coast Main Line, these were York, Durham and Newcastle – so the casualties could be transferred to horse-drawn road ambulances. Free talks about the story of the ambulance train are being given next Saturday at the National Railway Museum in York.

The first such train appeared during the Boer War in South Africa in 1899.

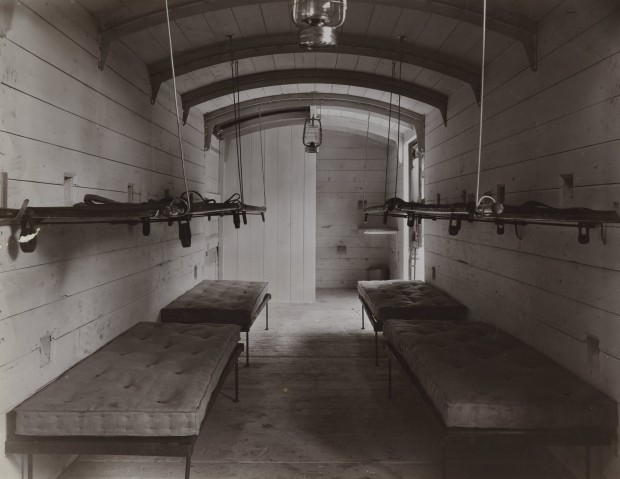

Inside an early, and rather rudimentary, First World War ambulance train. Picture courtesy of the National Railway Museum, York

When the First World War broke out, the UK Flour Millers’ Association presented the Red Cross with two ambulance trains, specially built and equipped, which were put to work in France in 1915.

However, if you were unlucky and you missed the purpose- built ambulance train, you could end up in a converted cattle truck.

In the museum’s archives is a diary written by an unnamed nursing sister on the Western Front. She wrote: “A train of cattle trucks came in from Rouen with all the wounded as they were picked up without a spot of dressing on any of their wounds, which were septic and full of straw and dirt.”

Many of the basics on the train appear to have been donated by well-wishers. She described how a matron had got the wounded men from Amiens “into cattle trucks on mattresses, with Convent pillows, and had a 20-hour journey with them in frightful smells and dirt . . . they’d been travelling already for two days”.

Soon, the War Office commissioned 30 “standard” ambulance trains, and most of them operated on the Western Front. Each “standard” had 16 cars, including a pharmacy car and two kitchens.

Each ward car contained 36 beds arranged in three tiers, so an ambulance train could accommodate about 400 injured men.

TIGHT SQUEEZE: Inside an ambulance train in April 1918 – the surroundings are almost luxurious, although the noses of those on the top of the three bunks must almost have touched the ceiling. Picture courtesy of the National Railway Museum, York

SOME of these new trains could even be described as posh – the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Company’s ambulance train was “finished throughout with white enamel”, and had the luxury of “fixed and portable fans”.

The unknown nurse travelled on such a train. “The 12 sitting up cases in each carriage are a joy after the tragedy of the rest,” she wrote.

An Illustrated War News picture of porters at Boulogne, France, carrying a soldier who has been wounded

in both feet to an ambulance train

“They sit up talking and smoking till late, because they are so surprised and pleased to be alive, and it is too comfortable to sleep.”

Of course, for the wounded men, however luxurious the ambulance train, the experience cannot have been pleasant.

The war poet Robert Graves, who was so badly wounded on the Somme in 1916 that his death was reported, wrote of his journey home on an ambulance train: “The Royal Army Medical Corps orderlies dared not lift me from the stretcher to a hospital train bunk, for fear of it starting haemorrhage in the lung.

“So they laid the stretcher above it, with the handles resting on the head-rail and footrail.

I had now been on the same stretcher for five days. I remember the journey as a nightmare.

“My back was sagging, and I could not raise my knees to relieve the cramp, the bunk above me only a few inches away.”

To learn more about the history of the ambulance train, visit the York museum next Saturday – although booking is strongly advised.