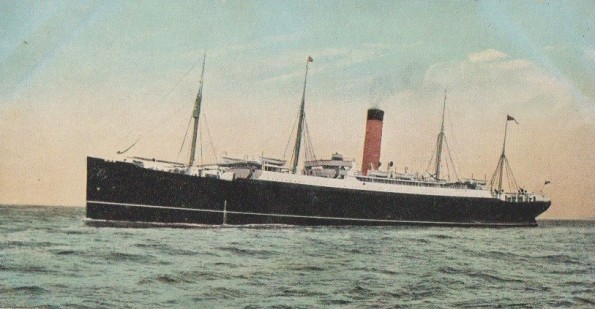

The SS Ivernia, which carried the Durham Pals from Egypt to France

Tony Kearney tells what the Durham Pals – volunteer soldiers from across the region – were doing 100 years ago this week, in the build up to their date with destiny: July 1, 1916, and the Battle of the Somme.

AFTER two months in the Egyptian desert, the Durham Pals knew they were about to be on the move again.

Rumours spread like wildfire throughout the battalion, most suggesting that they were bound for modern-day Iraq where around 8,000 British soldiers had been cut off in the town of Kut, about 100 miles south of Baghdad since the first week of December 1915. They were surrounded by the forces of the Ottoman Empire, and although a British relief operation had been launched in January 1916, it was in need of reinforcements.

So when on March 2, the 18th Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry clambered aboard dusty train trucks and on to Port Said, cheered on their way by the Mysore Lancers who lined the track, most expected their final destination would be Mesopotamia.

Instead, once at Port Said, they unexpectedly received new orders to hand in their desert kit – although the ordinary men in the Durham Pals didn’t yet know where they were heading.

So just over two months after they had arrived in Port Said, the battalion boarded ship and began the return in the direction of Europe.

In his war history of the battalion, written in 1920, Lieutenant Colonel William Douglas Lowe wrote: “The time in Egypt had been well spent: plenty of hard work, a good deal of marching in the heavy sand and a not too luxurious diet with a very limited choice, or rather supply, of refreshing drinks had combined to make the men very fit and, generally speaking, the battalion had learned to fend for itself, make itself comfortable and settle down quickly under new and sometimes none too promising conditions.

“There were also many pleasant memories of a lighter nature – the Turkish coffee, the bathing, the queer broken English of the small native boys who cried their papers or their wares”.

He concluded: “It was a good time and prepared us gently for the more serious work ahead.”

On March 5, the battalion embarked on the Cunard-liner SS Ivernia, built by Swan Hunter on the Tyne. Before the war, the ship had plied the immigrant route from the Italian ports to New York, but it was now converted into a troopship.

The ship immediately suffered engine problems and so fell behind by the convoy, meaning it was without the protection of Royal Navy destroyers.

After the Pals’ eventful journey to Egypt, which involved a fatal crash at sea and running battles with German submarines, it must have been a nervous time for the men below deck.

The battalion war history recorded: “The voyage in the Ivernia was far more comfortable than the outward journey: the men were not crowded and the feeding was better. The weather, however, was bad most of the way; still the voyage was entirely uneventful.”

It added: “We waited off Malta for orders then passed through the Straits of Messina and the beautiful narrows of Bonifacio, where we received a wireless that three submarines were active in the Gulf of Lyons”.

If at first the men thought they were bound for Mesopotamia, the rumour then turned to Salonika before finally it became obvious that they were heading for France.

Private William Weatherley, one of the Bede College teachers who volunteered at the start of the way, wrote home: “For some days now, it has been evident that our destination was France and having passed Sardinia we were looking forward to our arrival at Marseille. But a thick mist and a drizzling rain set in to spoil our views off the port and town.”

After seven days at sea, the Ivernia arrived in Marseille, then, as now, a busy and cosmopolitan port on the southern coast of France. But their welcome to France was not what they might have hoped for, when the Ivernia crashed into an Allied warship as it pulled into port.

Lieut Col Lowe wrote: “We reached Marseilles in bad weather on March 11 and concluded our voyage by running foul of a destroyer lying in the dock where we were to be berthed and by enjoying to the full the sulphurous remarks of her crew on the lineage and ancestry of our pilot.”