Some of the Belgian refugees in Middleton-in-Teesdale, in 1914

ON August 1, 1914, Germany declared war on Russia. On August 2, Germany demanded right of way across Belgium so that it could attack France, Russia’s ally.

The Germans claimed that the French were about to invade Belgium, but the Belgian king and parliament refused the Germans’ demand.

On August 4, the Germans marched in anyway, reaching the town of Liege. Under the terms of an 1839 treaty, Britain was obliged to protect Belgium’s borders from foreign invasion. Germany regarded the treaty as a “scrap of paper”. Britain declared war.

On August 16, the Germans captured Liege. On August 20, they captured Brussels.

They headed south towards France, and on August 23 they reached the town of Mons.

Here they met the British Expeditionary Force, and for the first time since the 1815 Battle of Waterloo, a few miles north, Britain was engaged in war on mainland Europe.

The British lost. The Germans marched on, reaching within 20 miles of Paris. They were forced back, and as September wore on they found themselves bogged down on the banks of the Somme.

So they opened up a second front. On September 27, they attacked the Belgian port of Antwerp. It was defended by the Belgian army which, at the beginning of August, had been 220,000 strong but was now down to 50,000. About 12,000 British marines assisted the Belgian remnants.

Fearing Antwerp would be over-run, the Belgian government called on Britain to take 500,000 refugees. And a few thousand were smuggled across the channel before, on October 9, the Germans captured the port.

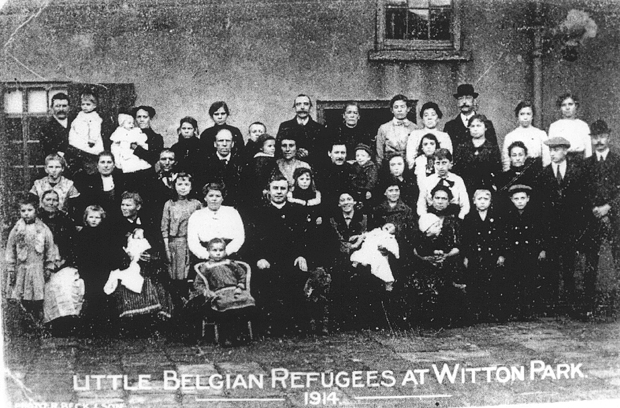

Belgian refugees pictured at Witton Park, County Durham, in 1914

But the Germans’ impetus was slowing. On October 29, they reached the border town of Ypres and fell into battle with the British.

And here they stayed for the next four years, slugging it out, heedless of the human cost, fighting from their trenches over hillocks and thickets.

But two million Belgians – a quarter of the country’s population – found it impossible to stay in their homes. They had proved plucky fighters as the invaders marched across their land, but this only incensed the Germans who responded with “Schrecklichkeit” – the horror.

On October 20, the first 100 or so Belgian refugees reached south Durham. As Echo Memories reported a fortnight ago, huge cheering crowds turned out at Darlington’s Bank Top station to greet the first, innocent victims of a war most still thought would be over by Christmas.

There were about 250,000 Belgians billeted in Britain during the First World War, with 6,000 alone living in a specially-built township in Birtley, near Chester-le-Street. Hundreds more seem to have been scattered across the south of County Durham:

ELDON: John Wilkinson, a manager at Eldon Colliery, took in Frans and Gertrude de Roack, and their 18-year-old daughter, Jenny, at his house called Eldon View. The de Roacks, like many of south Durham’s refugees, came from the town of Mechelen and they stayed in Eldon until the end of the war.

“They spoke often about it, and were always in contact with those people, and stayed friends forever,” says Germaena Verlinden, who is Jenny’s daughter and still lives in Mechelen.

“They came back home after the war. Their house was still there, but everything in it was stolen and it was a little damaged. My grandmother, Gertrude, had a ladies’ lingerie shop and everything had been stolen from that, too.”

They rebuilt their home and their business, and the lingerie shop was sold two years ago, as Germaena is now 79 and her sister, Martha, is 69.

Germaena said she thought a second Belgian family had stayed at Eldon. John Wilkinson’s grand-daughter, Doreen Webster, now lives in York and is still in touch with the Verlindens.

When Jenny Verlinden, left, was 18, she was a Belgian refugee who came to live in Eldon. Her daughter Germaena is on the right.

WITTON PARK: Perhaps the greatest concentration of Belgians stayed in Witton Park. On October 6, 1914, 43 refugees arrived in the village, making them the first in the region, and soon a total of 170 were housed there.

Their priest, Father Krajicek, became a well-known figure in south Durham as the unofficial leader of the refugees.

WINDLESTONE: About 20 refugees were housed in Albert Street, Windlestone, which the locals re-named Belgium Street.

MIDDLETON-IN-TEESDALE: There were several Belgian families housed in the Town Head area of Middleton-in-Teesdale. Many of the refugees had been fairly prosperous in their homeland and people in south Durham – many of whom, it should be remembered, had had no contact with foreigners – were pleasantly surprised that the newcomers were well-educated and polite. The photographs of the Middleton-in-Teesdale refugees, kindly sent in by Ronnie Walton and Bill Payne, show that they were well-dressed and essentially middle class.

WILLINGTON: J Brown of Crook writes: “Just after the Second World War, I was working in some wooden houses at Newfield, near Willington, and was told that the houses had been built for the Belgians.

“Maybe Newfield people have more information about them?”

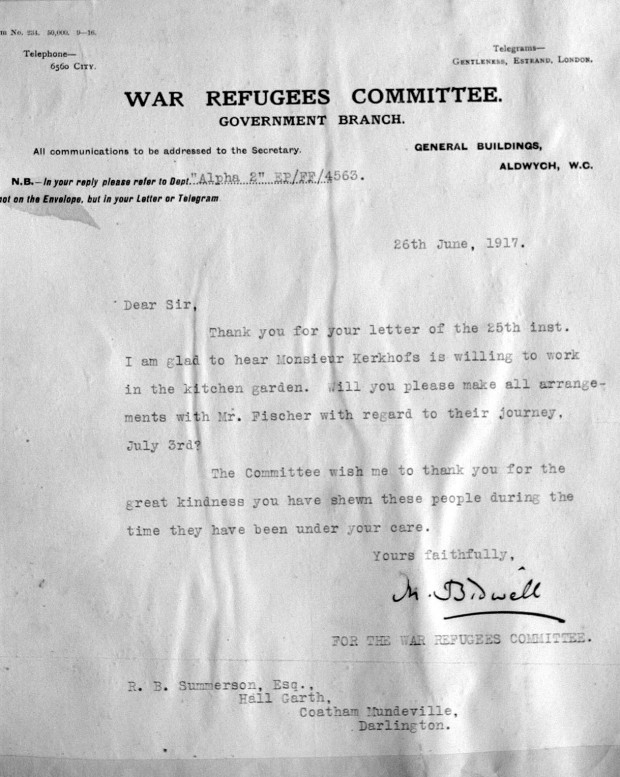

This letter, dated 1917, says that Monsieur Kerkhofs was at work in Coatham Mundeville Hall kitchen gardens

FERRYHILL: Some years ago, J Stephenson, of Newton Aycliffe, was researching her family tree. She came across an entry that said an unnamed Belgian child was buried in Duncombe Cemetery, Ferryhill. There was no more information, but it suggests that the Ferryhill area had its own refugee community.

HIGH CONISCLIFFE: Mrs Westoll had two houses full of Belgians in the village.

BARTON: The newly-built reading room was, for a while, home to 14 refugees.

COATHAM MUNDEVILLE: About 20 Belgians were housed in Coatham Hall. Mr Hardinge, the Hall owner, had given the building rent-free and Mr RB Summerson, of Hallgarth, paid for the refugees’ up-keep. There was no money from central government to assist with the refugees, so it was down to local communities to provide funds.

DARLINGTON: Because it was the largest town in the district, Darlington had wealthy inhabitants who were able to offer their country homes for refugee accommodation. Cottages in Redcar, Arkengarthdale, Cotherstone and Reeth were pressed into temporary use. The Grange Road Baptists found two houses, the nuns at St Augustine’s put up ten refugees. The Friends Meeting House, in Skinnergate, had room for 30. The mini-mansions of Oaklea, Woodlea and Thornfield also housed refugees, and Sir Frank Brown allowed them to live in Stanhope Road.

It seems, therefore, that south Durham was literally crawling with refugees, at enormous expense to the people who lived there. No one appears to have recorded their history, or how they were put to work to help pay for their upkeep.

We know that most of them went home in 1919, although it seems inconceivable that not one of them found love and stayed behind – for example, at Birtley, which has been researched by Durham University historians, we know that there are 30 families who didn’t go back.

Echo Memories has heard that in the North Road area of Darlington lived a Henry Daenams (or Daerams) until his death in the 1970s. He had two daughters.

Any information about Belgian refugees, or their descendants, in south Durham would be most gratefully received. Please write to Echo Memories, The Northern Echo, Priestgate, Darlington DL1 1NF, or e-mail chris.lloydnne.co.uk, or call 01325-505062. Thanks to all who have helped with the Belgians so far.